Newsbites (Page 5)

To Cheat, or Not To Cheat

The issue of plagiarism has always been a problem for universities. Traditionally, it has been up to professors and teaching assistants to identify possible plagiarists, but as the Internet has developed and evolved, cheaters have become increasingly sophisticated and students making honest efforts may feel at a disadvantage.

More than simple cutting and pasting, teaching staff now deal with material plagiarized from a diverse array of sources, including essay-writing services, online term paper directories and research-based websites. That's where Turnitin.com, a U.S. plagiarism-detection company, comes in.

Turnitin operates by comparing papers against three separate databases: an up-to-date archive of the Internet comprising billions of separate pages, the resources available from e-book and e-journal archives, and the collected papers it has received to date from students. (In peak periods, the influx reaches over 20,000 essays per day.) From that massive body of data and words, Turnitin returns a customized "Originality Report," a colour-coded, underlined and marked-up summary of each paper's use of material begged, borrowed, stolen - or original to the student. As a tool for detecting copied text, opinions and pithy opening lines, it is unparalleled: no human being could conceivably compare every word of an essay against so many sources.

McGill recently made headlines during its trial use of the controversial firm, whose services are employed by over 3,500 institutions in 50 countries. As part of the trial process, McGill obliged students in certain courses to submit papers they had written to Turnitin.com and to hand in the Originality Report before their papers would be graded.

McGill student Jesse Rosenfeld refused to submit papers to Turnitin and received zeros on three assignments. He challenged the result before a committee of the University Senate, which eventually decided that his papers should be graded by his professor. "What I object to most about the policy at McGill is that it treats students as though we are guilty until proven innocent," says Rosenfeld. Other criticism from McGill students has been that the service not only casts students as cheaters, but that it profits indirectly from a database built on their work.

Ironically, Turnitin.com founder John Barrie is a former professor whose impetus for starting the company was student complaints about the proliferation of cheating because of the Internet. (Reports from the University of Toronto say that Internet plagiarism grew from 55% of all academic offences in 2001 to 99% in 2002 in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.)

Morton Mendelson, associate dean for academic and student affairs in the Faculty of Science, argues the goal of McGill's use of Turnitin.com does not presuppose that all students are plagiarizing, but rather offers the University the means to detect those who are. "The logic here is to use Turnitin.com in the same way that screening is used at an airport or radar is used on the highway."

McGill's trial use of the service expired at the end of the year and now it is for the Senate to decide whether to continue with the company.

Studying Suicide

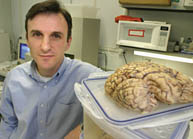

Dr. Gustavo Turecki.

Owen Egan

Each year, more than 1,200 people in Quebec kill themselves. It's by far the highest suicide rate in Canada and one of the worst in the industrialized world. Why this is the case is largely a mystery, one of many troubling uncertainties related to suicide. Dr. Gustavo Turecki, PhD'99, heads up a new multidisciplinary team of researchers determined to shed light on the risk factors related to suicide. The McGill Group for Suicide Studies, based at the Douglas Hospital's Research Centre, is trying to better understand what drives people to take their own lives.

"There is a real need for an interdisciplinary approach, because the answers aren't straightforward," says Turecki. "We know that certain disorders are clearly associated with suicidal behaviour - major depression, for instance. But not everyone experiencing major depression is going to try to commit suicide.

"Generally, research on suicide has focused on the social variables," adds Turecki. "But new evidence suggests that biological factors may also predispose people to suicidal behaviour."

Much of Turecki's own research examines the genetic underpinnings of suicide. He recently played a leading role in the discovery that suicide victims were four times as likely to have suffered from a genetic impairment affecting their serotonin levels. Serotonin plays a key neurochemical role in regulating mood. Still, Turecki acknowledges that this line of study will only get scientists so far. "I don't think we'll ever find a single gene that's responsible for suicide. There are a number of factors involved and that's why we need a more comprehensive approach."

Composed of neuroscientists, psychiatrists, geneticists, social scientists and others, the MGSS has some unique research tools at its disposal. The group owns one of the world's biggest collections of DNA samples from suicide victims. It also has access to the Douglas Hospital's Brain Bank, one of Canada's largest collections of autopsied brain tissues. Many of these are from individuals who committed suicide, enabling MGSS researchers to compare the brains of suicide victims with those who died of other causes.

"There are very few teams in the world equipped to look at suicide the way we look at it," says Université du Québec en Outaouais psychologist Monique Séguin, one of the researchers affiliated with the MGSS.

Baby, It's Not Cold Outside

The Arctic isn't what it used to be. Temperature increases in the west, thinning of the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean, receding permafrost, all point to one culprit: climate change, the more demure-sounding cousin of global warming.

Now, eight McGill researchers have joined a new research network called ArcticNet to study climate warming in the north. An Arctic meltdown will have enormous environmental and socio-economic consequences for Canada. It would have a devastating impact on animal populations and on the traditional hunting practices of northern societies. It would create severe coastal erosion. It could even present new challenges to Canadian sovereignty should the decrease in coastal sea ice lead to new intercontinental shipping in the High Arctic.

Illustration: Mark Lamarre

Because of this, the federal government established the $25.7-million ArcticNet program, with labs and researchers from across the country joining forces to study the changes, raise international awareness, and formulate policies and adaptation strategies for the once frozen North. The program is part of the government's Networks of Centres of Excellence, which builds partnerships between Canadian researchers from universities and the private and public sectors.

ArcticNet researchers will be collab-orating with teams in the U.S., Japan, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and several other countries, and the huge network involves 41 universities, 27 government departments, and two industrial partners. The McGill contingent includes Laurie Chan and Grace Egeland from the School of Dietetics and Human Nutrition, Evan Edinger and Wayne Pollard from the Department of Geography, Murray Humphries from the Department of Natural Resource Sciences, Jean-Eric Tremblay and Neil Price from the Department of Biology, and Ronald Stewart from the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences.

Members of ArcticNet will also work closely with Arctic residents, who are already dealing with the impact of climate change on their way of life. President of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Tom Brzustowski underscores the importance of this collaboration: "By involving Northerners in the scientific process, ArcticNet will train the next generation of scientists and Northerners urgently needed to ensure the stewardship of a new Canadian Arctic."