Epilogue

Looking for Lulu

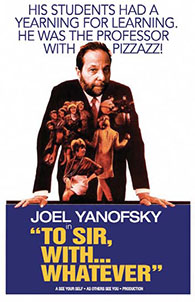

On the final day of class last spring, students in my magazine writing course at Concordia University asked if they could take me out for a beer. They'd liked the class, they said, and would be in touch. I won't say I rushed home to check my email, but I did keep replaying the final scene in To Sir with Love: the one where the teacher — Sidney Poitier — is rewarded for his dedication with the overdue affection of his previously delinquent students. I could practically hear Lulu singing, "Those schoolgirl days..."

When no one got in touch, my wife pointed out what should have been obvious to me after some 15 years, off and on, of teaching: my students had ulterior motives. "Their final grades aren't in yet, are they?" my wife asked.

"So what are you saying? They're just buttering me up?"

"Yes," she said, shrugging. I love my wife, but she's no Lulu.

The poet Robert Burns wished for the gift of "seeing ourselves as others see us," but that was before the Internet. Go online and you can find out what everyone thinks about everything, including you.

As a teacher you survive the semester by telling yourself your students aren't paying attention those mornings when your socks don't match, or you can't put two coherent sentences together. However, that was before MySpace. Now students are zeroing in on all our quirks and, quite possibly, videotaping them. I looked myself up on RateMyProfessors.com the other day and discovered a remark that stung and stuck: "Ummm, Joel, personal anecdotes do not a great course make."

As a teacher you also survive the semester by forgetting what it was like to be a student. I'd forgotten, for instance, how quick I was to judge my teachers, and how harsh I could be.

I took a poetry course in my final undergraduate year at McGill. It was held in a lecture hall which comfortably seated 80. Someone had clearly misjudged the interest of undergraduates in verse. There were just two of us registered. Despite that, the professor, punctual and well-prepared, took attendance every class; though, after a while, he did it silently.

My classmate and I sat next to each other in the centre of the room, but Professor H., let's call him, lectured as if the class was full. He would look to our left, our right, behind us, and then, finally, at us. It was like waiting for a rotating fan to get to the spot where you really needed it and then, once it arrived, watching it move quickly, inexplicably on.

Occasionally, either my classmate or I would ask a question about Emily Dickinson's reclusive nature or W.H. Auden's thoughts on suffering, but we never asked the question we really wanted answered: "What's the matter with you?"

Now I can offer an educated guess. Professor H. had probably been teaching for more than 20 years by then and was probably embarrassed by the unexpectedly low attendance. Last spring, in my class, sometimes only two or three students showed up and my method for coping with the awkwardness was to revert to personal anecdotes — like the one about Professor H.'s behaviour. It's always been my failing as a teacher: I try too hard to be liked. Professor H., to his credit, kept doing what he'd always done, no matter how odd it appeared.

As a result, I learned about some interesting poets and poems that semester, courtesy of Professor H.'s eclectic reading list and wide-ranging lectures. He also allowed me to do my final paper on Allen Ginsberg's Kaddish, a long poem about a mother's death, an experience I'd just been through myself. That assignment taught me that writing about literature didn't have to be a stuffy, detached reiteration of abstract terms. It could be subjective, intimate: a lesson that has, for better or worse, informed my work as a literary journalist. Even back then, I knew Ginsberg and my own personal ramblings couldn't have been in tune with Professor H.'s tastes, but he gave me an A-. In his written comments on my paper, he offered a prescient critique. He pointed out that my writing style was, perhaps, better suited to an audience outside the university.

I wish now I had talked to him about that, maybe offered to buy him a beer after class, but I didn't; I guess I'm no Lulu either.

Joel Yanofsky is an award-winning Montreal writer and the author of Jacob's Ladder and Mordecai & Me: An Appreciation of a Kind. His reviews and articles have appeared in the Walrus, the Village Voice, Canadian Geographic and the Globe and Mail.