A Mind for Music (Page 3)

Working as part of a research consortium led by Dr. Ursula Bellugi of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, Levitin is studying the musical abilities of Williams Syndrome patients in the hope of illuminating the possible independent relationship between musical ability and other cognitive abilities, with the long-term goal of furthering the understanding of how genes (or the absence of certain genes) affect brain function and behaviour.

Music and neuroscience are a natural fit, given Levitin's background. But what about comedy? Is there a place for humour in experimental psychology? Not so much. Not yet, at least.

"Music cognition is a somewhat new field, although it has historical roots going back to Pythagoras and, more recently, back a hundred years," says Levitin. "The very first experimental psychologists, the Gestalt school, were studying music. But compared to the number of people who are studying other things in psychology, like memory or vision, the number of people studying music processing is quite small. So it's a combination of something with an intellectual tradition but not a whole lot of people working at it that makes music cognition an attractive place to be. It's a fertile field with a lot of low-hanging fruit.

"But there's hardly anybody studying comedy. There's no paradigm as to the brain mechanisms responsible. Nobody's done the foundational work. It doesn't mean it's not interesting, but it'd be harder for someone to bootstrap their way up."

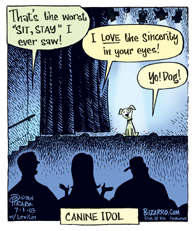

A Bizarro strip co-authored by Levitin. © Dan Piraro

Reprinted with special permission by King Features Syndicate

Which is not to say Levitin's forsaken comedy entirely. He occasionally test-drives new material in Montreal comedy clubs, and has a fresh sub-career on the go - contributing gags to Dan Piraro's popular Bizarro comic strip. Seen in over 200 newspapers internationally, Bizarro is widely heralded as the heir to Gary Larson's retired Far Side: one panel (except on weekends), a few words, and a whole lot of absurdist-punster yuks.

When Piraro printed his email address in the strip, Levitin, a longtime Bizarro fan, took it as an offer. "I wrote to him two or three years ago and said, ‘I have ideas for cartoons every once in a while. Would you like to hear them?' And he wrote back the same day: ‘What do you do for a living?' And I wrote, ‘I'm a research scientist.' So he types back, ‘Well, I have some ideas for experiments every once in a while. Do you want to hear those?'"

Levitin laughs at his own gall. "The funny thing is, being a research scientist is kind of like being a novelist. People are always accosting novelists - ‘I have this great idea for a novel' - as though the idea is the hard thing to come up with. Science is much the same; ideas are a dime a dozen. The questions are whether they'll advance the field, are they based on solid theoretical foundation, are they doable?

"Apparently it's also the same with cartoonists, but I didn't know that!"

Levitin persisted, Piraro relented, and the rest, as they say, is desert-island gags and clown jokes. Levitin has contributed to 40 Bizarro strips in the past 18 months, sometimes offering up fully realized material, sometimes jump-starting a soggy idea. A handful of somewhat "bluer" Levitin-Piraro work recently appeared in Playboy.

Levitin and McGill music student Meredith Robson of the Blue Monkey Project.

courtesy Dan Levitin

Most professors don't have gold records, or original comic-strip artwork, hanging in their offices. Most don't finance their graduate studies by remastering the Steely Dan back catalogue, or spend their free time penning punchlines. Still, Levitin doesn't think his polymathic interests are that unusual.

"There are a lot of people in this department that have interesting backgrounds," he insists. "One of the things you find at places like McGill, or Harvard, or Oxford, is people who have a real passion for life. That's how they got to where they are. They absorb everything they come into contact with and write about it, synthesize it, experiment on it."

He bolsters his argument with a laundry list of his colleagues' backgrounds and skills. Psychology professor and Canada Research Chair Jeffrey Mogil played keyboards in a rock band called 7 Minutes, who were once signed to A&M Records. Social psychologist Mark Baldwin was the host of Camp Cariboo, a popular kids' TV show. Chair of Psychology Keith Franklin "is one of these guys who excels at everything he attempts: pouring concrete, hanging drywall, electrical contracting, plumbing - not to mention neurochemistry and playing blues guitar."

"I guess my own interests are wide-ranging compared to a lot of people, but I don't think I'm special."

It's all, he says with a shrug, relative.

"I have a friend named E, who is the lead singer of a band called the Eels. I recently had lunch with him in Los Angeles, and he was saying, ‘Oh, you've got it made! You've really got the life! You're doing exactly what I want to do!' And I said, ‘You're crazy, man - you're doing exactly what I want to do.' He's big enough that he makes as much money as he wants, but he's not so big that he can't walk around Hollywood. People don't notice him on the street, they don't know who he is.

"He thinks I've got the perfect career, and I think he's got the perfect career." Levitin chuckles. "Life always looks greener on the other side."