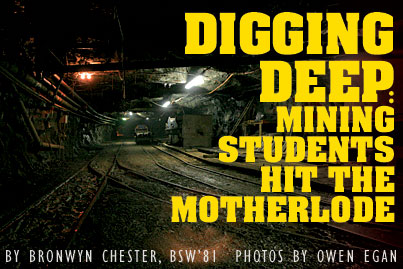

Digging Deep: Mining Students Hit the Motherlode

Digging Deep: Mining Students Hit the Motherlode McGill University

User Tools (skip):

It's damp and dirty work, but going underground provides McGill's mining engineering students with a golden opportunity

Sweat drips from under Philippe Goubau's hard hat as he pushes along a half-ton rail wagon. The wagon is filled with 14-foot drilling bars used to place explosives deep inside gold ore. It's not the heat that makes him perspire; deep in the Mouska gold mine, the temperature is a damp 12 degrees Celsius, even in June. Goubau's sweat is the result of hard labour.

As part of a unique undergraduate program, the McGill mining engineering student finds himself 450 metres below the earth's surface, hoisting supplies out of one elevator and placing them in the train that "trams" them along a kilometre of tracks to the next elevator, or "cage," so they can be sent down a further 500 metres.

At the second elevator shaft, Goubau (above) and other miners transfer the goods back from wagon to cage. The supplies are then distributed to various levels below: miniature railway ties where track is being built; cement to reinforce rock that's already been mined; explosives and detonators for another level. Later, he'll be helping to "skip the ore out of the mine," or getting it into the cage to be transported to the surface.

"There's a lot of loading and unloading in this mine," says Goubau. "If they'd known how deep the vein runs here, they probably would have sunk the shaft all the way from the top. Still, in a mine as rich as this one, with 14 grams of gold per ton of ore, the cost in labour is worth it for the company.

"The price of gold is high now," adds Goubau. "At $440 U.S. per ounce, it's worth mining. Last year, I held a brick of gold in my hands worth $600,000."

For a 19-year-old, Goubau speaks with some authority. This is his second work term out of the four he will do in McGill's co-op program in mining engineering. For the first two, students are assigned jobs that acquaint them with the work done by miners.

"We do this so that in the future they appreciate the work done by the people they'll be supervising," says Professor Ferri Hassani, director of the mining engineering program that's part of McGill's Department of Mining, Metals and Materials.

According to Hassani, the sort of grunt work that Goubau is performing at Mouska is quickly becoming a thing of the past. "Most mines today are highly mechanized, where the miner is more likely to be operating a machine, either in the driver's seat or remotely at a computer terminal." Mining has increasingly become a high-tech pursuit, says Hassani, and mining engineers routinely use highly sophisticated software programs to interpret drilling data and to create detailed models of mines that are used to plan the extraction of ore.

Goubau saw the high-tech side of mining last year during a summer spent at the Musselwhite gold mine, 600 kilometres north of Thunder Bay. One of his jobs was to operate the "scoop," a 12-metre-long front-end loader whose bucket "could hold a Toyota Echo's worth of muck," says Goubau.

"That was a completely different experience. There were 40-ton trucks underground hauling the muck [blasted rock] up to the surface. It wasn't nearly as physical as this mine," he says, explaining that it's only because of the particularly concentrated and narrow vein of gold at the Mouska mine, coupled with its geological instability, that miners still use such old-fashioned tools as the "jack leg," a hydraulic drill.

While working at the Musselwhite site had its advantages - "Saving money was a breeze given that the mine was dry and there was nowhere to go for two weeks," he laughs - Goubau appreciates the more familial atmosphere of the Mouska mine and the fact that he can do a variety of jobs. After his time as "cage man," operating, loading and unloading the elevator, he scooped muck, using a mechanical shovel, in the "drift," the miner's term for tunnel.

He's got two more years of study, but Goubau is already thinking about where he wants to end up. "I'd like to work for a big international contracting firm, like Redpath, where they send you all over the world designing and building mining equipment underground," he says.

Goubau, who grew up on an Ontario dairy farm where tough physical labour is part of life, is unusual among mining engineering students. "Most of our students are from the Montreal area and come from pretty urban backgrounds," says Hassani. "What helps them is having a spirit of adventure, a desire to apply what they've learned and the ability to work in a team." He emphasizes that the latter point isn't just about fostering good working relations - poor teamwork can have potentially lethal consequences.

"You've got a little city to run and if you're not together and working as a team then the mining operation is not efficient and you might compromise safety, which is a number-one priority in every mine in Canada," says Hassani, a specialist in rock and soil character.

One of Goubau's Mouska co-workers is fellow McGill student Catherine Chu. She's underground two to three days a week, working with a laser-based surveying device called a cavity-monitoring system to locate elusive bits of gold ore left after "mocking," or after the easier-to-find ore has been removed after blasting.

The work placements played a pivotal role in convincing Chu to pursue a mining engineering degree. "I like the fact that I can earn money and gain job experience while I'm studying," she says. Students typically exit the program with little or no student debt, some impressive work history for their resumés and, if the price of metals and minerals is heading in the right direction, a job offer in their pocket. A drawback is that students get virtually no time off. Between courses and work placements, they're busy for most of the year.

The work placements can be eye-opening, especially for students who have never experienced a blue-collar environment. Angelina Mehta, BEng'97, MBA'02, remembers the first time she toiled underground in a gold mine near Val d'Or, Quebec. The self-confessed city girl quickly realized she was the only woman there and the only non-white miner to boot.

"I suddenly thought: What the hell am I doing here?"

Mehta recovered her bearings, and the next summer found herself driving a 200-ton truck in an open-pit molybdenum mine in British Columbia. The following year, she worked at a rock mechanics lab in Ottawa. Her final term was spent in Sudbury, Ontario, doing research on underground water for Inco. Today, the Montreal-based Mehta is an internal consultant with Lafarge North America, the giant French cement and construction materials company. Not bad for someone who confesses, "I had no love for rocks" when she began her studies.