A rural revolution

Macdonald College plant science experts circa 1911 (left to right) Leonard Klinck, G.H. Butler, Robert Summerby and Paul Boving. Jimmy Coull is ploughing the field behind them.

McGill Archives

Since its founding 100 years ago, Macdonald Campus has turned agricultural studies on its head — and sent thousands of grads out into the world armed with a great education, a roll-up-your-sleeves attitude and priceless memories.

BY MARK REYNOLDS

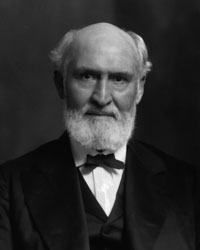

Sir William Macdonald was a man of contradictions — the very model of Victorian probity, yet deeply anti-religious; living like a “streetcar conductor,” yet donating sums to McGill University that were staggering, even by today’s standards. He alienated relatives and business partners, yet once spent hours, entranced, watching a tiny chick peck its way out of its shell. One contemporary labelled him, “a paragon of paradoxes.”

Macdonald College's founder Sir William Macdonald

Notman Photographic Archives

No fan of pomp and circumstance, Sir William avoided the spotlight. That wasn’t at all true for the man who joined forces with him to launch Macdonald College (now Macdonald Campus), in a partnership that would revolutionize agricultural education in Canada.

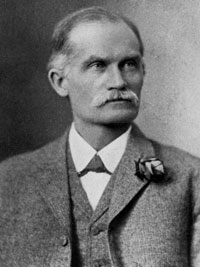

James W. Robertson was the federal government’s commissioner of agriculture and dairying when Macdonald met him in the 1890s. A natural-born showman, the flamboyant Robertson once arranged for a 10-ton chunk of cheese to be displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 to promote Canada’s dairy industry.

Macdonald College's first principal James W. Robertson

McGill Archives

While Macdonald and Robertson made for an odd couple in many respects, the two men shared a common cause. At the end of the 19th century, rural education was in shambles. Populations were too dispersed, teachers too scarce, and facilities too poorly maintained to effectively educate students.

Through his work as commissioner, Robertson was keenly aware of the situation, as was Macdonald, a native of rural Prince Edward Island who believed deeply in the benefits of education.

Sir William, with Robertson’s assistance, established the Macdonald Manual Training Fund. Between 1903 and 1905, Macdonald-funded institutions appeared in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario and Prince Edward Island. By 1907, more than 20,000 children were receiving the benefits of what became known as the “Macdonald-Robertson Movement.”

Macdonald College would become the movement’s crowning achievement. Beginning in 1904, Sir William assembled 561 acres of farmland on Montreal’s West Island, spending $1.5-million in the process. When the school opened its doors in 1907, he provided an additional $2-million endowment for operating costs. The London Times proclaimed that the college would “differ very widely not only from the educational institutions of the Old World, but also from most of those previously existing in the Dominion.”

Macdonald was considered unique because it reflected Sir William’s belief that a healthy, happy society rested on the three pillars of “farm, home and school.” As a result, the college included a School of Agriculture, a School of Household Science, and a School for Teachers.

Robertson presided as principal when the first 215 students started classes in the fall of 1907. Despite Macdonald’s support, funding was tight, and while the visionary Robertson had many strengths, finances were not his forte. He resigned in 1910 over philosophical differences with Macdonald. The founder insisted that the college tend to the agricultural interests of eastern Canada, while Robertson wanted Mac to play a larger role on the national and international stage. As the college progressed over time, it would distinguish itself by doing both.

BUILDING A BETTER PIE

Though the early years had their bumps administratively, Mac researchers were productive right from the start, breeding new varieties of clover, alfalfa and soybeans. Robertson’s influence extended well beyond his short tenure, largely due to the stellar team of professors he assembled. This initial group included such influential and productive minds as the cereal-breeding pioneer Leonard S. Klinck, who developed Pontiac barley and the Banner 44 variety of oats, and Frank C. Harrison, the agricultural bacteriologist behind a 1914 landmark study of Montreal’s milk supply.

If you are what you eat, there’s a bit of Macdonald in each of us. The juicy stalks of the hardy Macdonald rhubarb, developed by Professor Harold Murray in the 1920s, are still favoured by many a pie connoisseur today. Plant scientists Emile Lods (Mabel and Roxton oats and Oxford barley) and Martin Raymond (Iroquois and Algonquin corn) became known internationally for the resilient cultivars they bred. More recently, former Mac scientist Shahrokh Khanizadeh, MSc’84, PhD’89, and former dean Deborah Buszard developed the popular Chambly strawberry, specially designed to withstand Quebec’s stern climate while retaining its appealing flavour.

Macdonald’s current dean, Chandra Madramootoo, BSc’77, MSc’81, PhD’85, says that Mac has played an essential part in the evolution of agriculture in Quebec, but its contributions have been largely unsung. “We were a success story people didn’t know about.”

In the sixties, for instance, Macdonald soil scientist Angus MacKenzie introduced the province’s farmers to a more scientific approach to nurturing their land — which fertilizers to use and when, for instance — so that it could nurture growth in return. The soil-testing service he established at Mac became the model for all government soil-testing laboratories in the province.

MOXLEY’S MOXIE

While MacKenzie helped Quebec farmers boost crop yields, Macdonald animal scientist John Moxley, the man chiefly responsible for creating Mac’s Dairy Herd Analysis Service (DHAS), transformed milk production in Quebec.

Macdonald College in 1908.

Notman Photographic Archives

In the fifties and sixties, the Quebec dairy industry was in dire straits, ranking among the lowest producers in the country. Today, the province’s cows churn out three billion litres of milk a year, 38 per cent of Canada’s dairy production. “Quebec could not have done that without John Moxley. The gap between where the industry was when John began his work and where it is today is enormous,” says Madramootoo.

The far-sighted Moxley looked at both genetics and environmental factors to solve the puzzle of Quebec’s underachieving bovines. He criss-crossed the province in his own car, collecting samples, then helped construct computer programs (themselves a novelty) to analyze the data he assembled. He convinced farmers to improve the feed they were offering their cattle and, after settling on the genetic traits that Quebec cows needed in greater abundance, designed an artificial insemination program. “Forty years later, terms like biotechnology and genomics have become popular buzzwords. John Moxley was probably one of the first specialists and we didn’t realize it at the time,” says Madramootoo.

The DHAS has since evolved into Valacta, a partnership between Macdonald Campus, the Quebec government and the Quebec dairy industry, that ensures that Quebec’s dairy producers continue to have access to the sort of expertise that Moxley began providing decades ago.

A “RADICAL BREAK”

By 1929, with research on a roll, the academic leaders of Macdonald College turned their attention to reinventing agricultural education. A faculty committee tabled a report that longtime Mac professor John Snell, in his book Macdonald College of McGill University, called “a radical break with tradition in the matter of courses normally offered to students in agriculture.”

And it was radical — all credits for applied courses were eliminated and classes focused on basic biological and physical sciences (and English) for the first two years of the agriculture program. “That had an enormous impact,” says Roger Buckland, BSc(Agr)’63, MSc(Agr)’65, Mac’s dean from 1985 to 1995. The change brought Macdonald’s undergraduate programs new respect and served as a model for other agricultural institutions in Canada.

By the late 1950s, there was little doubt that Macdonald was Canada’s pre-eminent agricultural college. Close to 20 per cent of all the undergraduates and almost 50 per cent of doctoral students studying agricultural science in Canada were at Mac. “Macdonald College produced the first PhDs in agricultural subjects in Canada, and has, through the past half-century, graduated more than all other Canadian institutions combined,” declared then-dean H.G. Dion in 1959.

Buckland himself came to Macdonald as a student because of its emphasis on basic science. “That, and I had heard that the ratio of female students to males was seven to one, because of the education department,” he adds with a laugh.

He wasn’t disappointed on either front – his future wife turned out to be “one of the seven,” and Buckland would go on to teach as a professor of animal science at Macdonald, before becoming dean.

CLOSE-KNIT CLAN

While Mac pursued high ambitions for its teaching and research programs, campus life on the largest green space on the Island of Montreal was — and remains — cozy. Investment dealer J. William Ritchie, BSc(Agr)’51, now retired, describes the Mac family as a “clan” in the true Scottish tradition. “We worked, lived, played and loved together. We became friends regardless of race, religion or the part of the world from which we hailed.”

Madramootoo, who grew up in Guyana, also found an inviting home. “We would all — students from Africa, India, China — cook together and share our meals. Everyone would sit together and talk about everything under the sun.”

Buckland remembers the Macdonald community of his student days as tight-knit and friendly. Most students lived on campus. Many faculty members did too, or, at least, they lived close by. Professors would often invite students over for dinner.

Which isn’t to say that everyone always behaved at their best. Stephen Casselman, BSc(Agr)’68, for many years a CBC agricultural commentator, recalls how his class tormented the staff by conducting frequent panty raids, “misplacing” all the cafeteria’s cutlery, and taking joyrides on manure spreaders. “In our day,” he says, “we believed that education was more than books and, as a result, comradeship meant doing things together.”

A LABOUR OF LOVE

The pastoral surroundings of the campus have long been perfect for the sort of lazy strolls that cement friendships. They also provide a vibrant, growing field laboratory, thanks to leaders who saw the value of preserving the island’s disappearing green space.

Professors and students looking for William Brittain, BSA’11, dean of agriculture and vice-principal of Mac from 1934 to 1955, often had to don gumboots and wade through the muck and mud of the evolving Morgan Arboretum to find him.

A jogger enjoys the beautiful surroundings of the Morgan Arboretum

Nicolas Morin

Though an entomologist by training, Brittain, one of Macdonald’s earliest graduates, was passionate about horticulture, and he believed Mac’s teaching and research activities would benefit greatly if the college could acquire an expanse of natural woodland. Brittain sparked the interest of some prominent Montrealers, including Cleveland and James Morgan (owners of Morgan’s department stores) and Montreal Star publisher J.W. McConnell, whose support allowed for the purchase of nearby property. The land for the arboretum, assembled by the Morgans, was officially turned over to McGill in 1945.

William Brittain

Mcgill Archives

Brittain personally acquired many of the exotic trees now growing there (he was especially fond of birches). Today, the 245-hectare arboretum continues to serve Mac’s research and teaching needs, while providing a home to a dizzying array of trees and shrubs, 30 species of mammals, 20 species of reptiles and amphibians, and more than 170 species of birds. About 30,000 visitors travel to the arboretum each year, coming to ski, hike, bird-watch or take in the fall colours.

TIME OF TRANSITION

The late 1960s and early 1970s were an edgy period for Mac, in the wake of a Quebec government report that recommended that the Faculty of Agriculture be moved to the downtown McGill campus, freeing Mac’s land for a West Island CEGEP. A McGill report written in response, and unanimously accepted by the University’s board of governors, concluded that “the transformation of the Macdonald Campus to a CEGEP would lead finally, and probably relatively rapidly, to the disintegration of the Faculty and the ultimate loss by the University of the entire Macdonald site.”

David Stewart, whose family were heirs to Sir William Macdonald’s estate and had continued their generous support of the college after his death, stepped forward and led the resistance. “He opposed the move and made that adamantly clear,” says Buckland. The family threatened legal action to reclaim the land and endowment if the move were to take place. Stewart also offered to provide most of the funds needed for a new Faculty of Agriculture building, as long as it was constructed on the Mac campus.

In the end, the campus stayed put, though the education faculty was moved downtown and a significant portion of land was leased to John Abbott College. The uncertainty took its toll. “We did lose young, energetic faculty to institutions that were more stable, and enrollment went down,” recalls Buckland.

But with the opening of the Macdonald-Stewart Building in 1978, the downturn swung back up. For the first time in its history, the campus became home to more than 1,000 students.

NEW NAME, NEW MISSION

In 1991, Macdonald officially became home to the newly renamed Faculty of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. The timing was excellent. With the 1992 Rio Earth Summit just around the corner, environmental issues were moving to the forefront of both public and research priorities.

Deborah Buszard — dean of the faculty from 1995 to 2005 — says that Mac’s students were quick to embrace their faculty’s fresh orientation. While wondering what to do with the 30-year old Robertson Terrace, a residence building that was becoming increasingly derelict, Buszard was approached by a group of students with an idea for promoting ecological living on the campus. They wanted to “try living together in an environmentally friendly way, reducing their impact on the environment,” recalls Buszard.

The result was the transformation of Robertson Terrace into the EcoResidence. Created out of almost completely recycled materials and featuring state-of-the-art heating and ventilation systems to maximize energy conservation, the award-winning EcoResidence became the first residence of its kind in Canada.

Though Buszard is now a biology professor at Dalhousie University, Mac still holds a special place in her heart.

“Mac’s role has always been to serve the needs of people, through education and the creation of new knowledge,” she says. “Today [that mission] is probably more important than ever. We need to apply really good science and technology to issues like global warming, soil and water conservation, environmental health, diet and nutrition. Today that role is global.” With files from Brett Hooton, BA’02, MA’05, and Kathe Lieber, BA’71

Tales from the home front

Household science students circa 1913, busy at work in their infamously unfashionable green and white striped gingham uniforms

McGill Archives

The photos of students in the School of Household Science look almost impossibly quaint to modern eyes – rows of identically dressed women ironing, sewing and cooking in tandem. But those crisply starched aprons belied a serious academic purpose: the introduction of scientific rigour into nutrition and household studies.

When Sir William Macdonald announced that “household education” would be one of the three pillars of the College’s curriculum, a Toronto newspaper applauded his effort, pointing out that, despite recent social and technological advances, “on many a farm the windmill sends the water to the cattle while the old-fashioned pump is good enough for the housewife.” Forced by isolation to be self-sufficient, rural women in particular needed strong domestic skills to survive, let alone thrive.

In 1907, 62 women signed up for the School of Household Science’s first classes, which were originally designed to help young women make “sanitary, comfortable and happy homes in the country.” But Katherine Fisher, head of the school from 1910 to 1917, quickly recognized that “a knowledge of the sciences” was key to giving the discipline “a position of dignity,” and refined the curriculum accordingly. The two-year diploma in institutional administration, first granted in 1912, fulfilled an urgent need for qualified managers of food services in the military during WWI, and many graduates went on to become prominent in the new field of dietetics.

Today, the School of Household Science lives on in the form of Mac’s School of Dietetics and Human Nutrition and the Department of Food Science and Agricultural Chemistry. Graduates in the former go on to use their expertise to promote healthy eating in a wide variety of settings, including schools, clinics, hospitals and seniors residences. These grads are prized for their abilities, says Dean of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Chandra Madramootoo.

“At every convocation, representatives from the Ordre professionnel des diététistes du Québec [the licensing body for dieticians in the province] tell me how terrific our graduates are.”

The teacher's teacher

If a single figure could embody the years during which McGill’s teacher training program was located at Mac, it would undoubtedly be Sinclair Laird, the man who headed the program for 36 years, between 1913 and 1949. Handpicked by Sir William Macdonald himself, Laird was trained in both Scotland and France. Macdonald College historian Helen Neilson described Laird as some- thing of a benevolent despot — paternalistic in his devotion to his students, autocratic in how he ran his school.

Laird had firm ideas about how a teacher-to-be should comport herself. There was never any excuse for dirty fingernails, and if he spied a little too much leg upon entering a classroom, he would thunder, “Ladies, please pull down your skirts!” Laird also displayed ample imagination as an educator. He was among the first to advocate for such classroom innovations as using audio-visual methods to supplement lectures, introducing musical activities in schools, and using current events to spur classroom discussions.