Nobody Does It Better

Dave Reginek DRW/NHL 1

Mike Babcock is one of the most respected coaches in the world of hockey. Some of his best work, though, takes place away from the rink.

BY NEALE MCDEVITT

Mike Babcock, BEd'86, is the very picture of success. The Detroit Red Wings coach led his charges to a Stanley Cup championship last spring, picking up a nomination for the Jack Adams Trophy as the National Hockey League's coach of the year in the process. Under his leadership, the Red Wings have won at least 50 games in each of the last three seasons. Only five other coaches in NHL history have steered their teams to back-to-back 50-win campaigns, and they include Hockey Hall of Famers Scotty Bowman and Glen Sather.

Babcock will be the first to admit, though, that he took a rather circuitous path to the top of the mountain.

In the late 1980s, he was living what he calls "a beer commercial lifestyle." Having completed his McGill degree in physical education, he had no great desire to get a job or settle down. "Growing up in Saskatoon, a lot of people I knew went down the same road; they got their degree, married a girl from their class, found a job and had three kids before they were 25. That wasn't for me. I wanted to get out and experience the world a bit. But I really didn't have a plan."

For a hard-scrabble defenceman (albeit an all-star at the university level) and former captain of the McGill Redmen, that meant signing on with the Whitley Warriors, a semi-pro hockey team in Northeastern England. Just a few years removed from a tryout with the Vancouver Canucks, Babcock found himself in hockey's remotest backwater—and he loved it. "It was a year of playing, training and having fun," he recalls.

When he wasn't schooling his British teammates on the finer points of a good "face wash" (in hockey terms this involves making your gloves as repulsively stinky as possible, then introducing them to your opponents' mugs) or buying cheap cars at auctions to resell them at a profit, Babcock taught special ed at Northumberland Community College even though, in his own words, "I knew nothing about special education." It wouldn't be the last time Babcock talked himself into a job he knew little about.

A year later, Babcock found himself back in Saskatchewan living at his father's lake home "not doing much of anything." When his brother-in-law showed him an article about a vacant hockey coach job at Calgary's Red Deer College, Babcock finally hatched a plan—a modest one, but a plan nonetheless. "I figured I'd apply for the job just to get a free trip to the Calgary Stampede," he says.

But a funny thing happened on his way to the rodeo; Babcock became a hockey coach. Changing out of his cowboy duds at a high school across the street into more conventional wear, he aced the interview—much to his own surprise, and chagrin. "I remember leaving and thinking to myself, Oh my God, I'm going to get the job. Now what?" he laughs.

COACHING 101

Mike Babcock sporting his McGill tie behind the Detroit Red Wings bench.

Dave Reginek DRW/NHL 1

Babcock went straight to an under-17 hockey camp in Calgary. Armed with a pen and a large notebook he sat in the stands every day, diligently writing down every single drill, a harbinger of the work ethos and attention to detail he is renowned for today. "I didn't know what I was doing," he admits. "But I did know if you played hard and had fun, you always had a chance of winning."

And win he did. In 1989, Red Deer won the provincial collegiate championships and Babcock was named coach of the year.

It's been an oft-repeated pattern over the course of his two decades of coaching—success has followed him at every level. In 1993, Babcock took the helm of the University of Lethbridge hockey program, leading the Pronghorns to their first ever Canadian national university title. His six years as head coach of the Western Hockey League's Spokane Chiefs saw him earn West Division Coach of the Year honours twice. And Babcock is the only Canadian coach to win both the world junior championships (in 1997) and the world senior title (in 2004).

In the NHL, his rise as a coach has been nothing short of meteoric—beginning in 2002-03 when the rookie bench boss led the Anaheim Mighty Ducks to the Stanley Cup finals only to lose in game seven to Martin Brodeur's New Jersey Devils. Babcock has compiled 162 regular season victories in his first three years in Detroit—an amazing run that hasn't gone unnoticed by Detroit general manager Ken Holland. "We've done a lot of winning under Mike's watch," said Holland after rewarding Babcock earlier this summer with a new three-year contract worth some $4.5-million. "He's been a great fit for us."

Babcock coached Team Canada to a world championship in 2004. He is seen here with two of the players from that squad, Ryan Smyth (left) and Scott Niedermayer.

Chuck Stoody/CP Photo

ROBBING AND DOING

When asked about his success, Babcock deflects praise as deftly as he used to block shots in front of the Redmen net. "I'm a big R&D guy—I Rob and Do. I steal from the best coaches in whatever league I'm in," he laughs. "When I first started in Anaheim we played an exhibition game against the Minnesota Wild and Jacques Lemaire. In the pre-game skate I noticed they were skating 700 miles an hour faster than us. The next time our teams played I snuck into the building so I could watch him run practice and I got some great ideas."

However, he is quick to credit his alma mater with helping lay the foundation of his success. "At McGill, the guys I ended up being tight with were way more academically oriented than I was," says Babcock. "I had to get a 3.5 [GPA] in my first term and I really learned how to apply myself academically like never before. But I learned just as much from the people I met there and the conversations we had. I believe in lifelong learning. We get better every day or, next thing you know, some other guy has your job."

Babcock wears his love of McGill on his sleeve—well, at least around his neck. Few McGill alumni are as penly proud of their alma matter as Babcock, who often wears his McGill tie behind the Red Wing bench for important games.

"I wasn't sure what I wanted to do with my life, but going to McGill helped me understand that whatever I chose to pursue, no matter how big, it was there for me if I was just ready to reach out and grab it," he continues. "If you don't dream, you cap your potential and the best thing about the dreams I'm living now is that I'm in control of them. McGill taught me, if you work hard, you prepare hard and you do good things, then good things will happen to you."

Of course school pride only goes so far. When asked why he wasn't wearing his lucky McGill tie for Game Six when the Wings clinched the Cup, Babcock laughs. "I wore it the game before when we lost so I put it in mothballs. I don't fool around with that stuff." His record with the tie previous to that loss was 4-0.

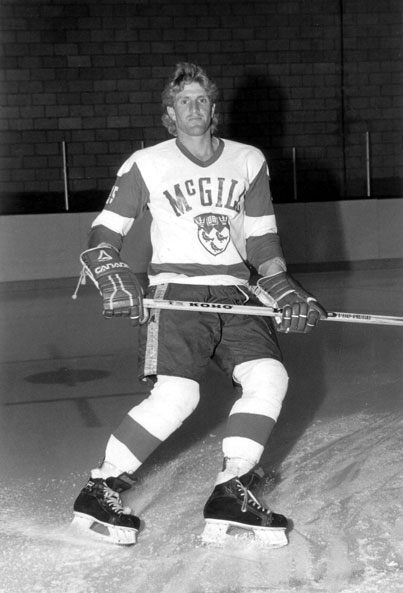

Babcock during his playing days with the McGill Redmen.

McGill Athletics

TURNING TRAGEDY INTO SOMETHING BEAUTIFUL

Talking to Babcock's colleagues, players and former teammates, it is clear that his coaching strength goes beyond a lucky tie and a few nifty drills he's piked from rivals.

"He's got tremendous passion and intensity," says Holland. "Mike and I share the same outlook; the only thing that matters is team success."

"Babs is a hard-ass," says Jarrod Daniel, BSc'99, who played goal for Babcock in both Moose Jaw and Spokane during the coach's time in the Western Hockey League (WHL). "Guys weren't scared of him, but we respected his honesty and work ethic so much that we were afraid of letting him down. He's a great guy to play for, not just hockey-wise, [but] for the fundamentals of life. As great a coach as he is, he's a far greater man."

As Daniel approached his 20th birthday, at which point he would be too old to continue in the WHL, he had to make a choice: play in the minor leagues or go to university. Babcock remembers Daniel standing out from the other players because he was "a real brainiac." He convinced the young netminder to go to McGill, where he earned his undergraduate degree in anatomy and cell biology in 1999.

Today Daniel is a surgical resident at the Mayo Clinic. "My mother used to talk to me and my sisters about being difference-makers, about making an impact in the world. People like Jarrod are real difference-makers," says Babcock, pride evident in his voice. "I just coach hockey, for crying out loud."

Not surprisingly, Babcock undersells his own impact on people's lives.

This past March, Daniel was working with a nine-year-old girl with metastatic osteosarcoma, a malignant bone cancer, on both of her lungs. As he was wheeling her to the operating room where doctors would remove a series of tumours from her lungs, Daniel noticed she was wrapped in a Detroit Red Wings blanket. "When I told her that Babs was a good friend of mine, her eyes lit up and we really hit it off," says Daniel. "She basically lived, ate and breathed the Detroit Red Wings."

Daniel asked her if she could give the team one message, what would it be? "When they make it to the finals," she said, "you tell them to fight like it was their last game." Daniel emailed the message to Babcock, who, in turn, hung it on the dressing room wall as inspiration for his players.

Just prior to game three of the Stanley Cup Finals, Babcock called the girl from his Pittsburgh hotel and the two talked hockey at great length. A few days later, she received a Red Wings jersey signed by the entire team. "It was a great gesture on Babs' part," says Daniel. "The family said she was ecstatic and that it gave her a huge pick-up. She's fighting a cancer that will probably be terminal and this gave her a little boost, a little bit of confidence, a little bit of happiness."

Babcock has a special affinity for cancer patients. His mother died of cancer when he was 28 and two close friends of his lost young sons to the disease. "Those things don't keep happening unless you're supposed to do something about it," says Babcock. "At some point, you have to say 'wakey-wakey.'"

While coaching in Anaheim, he met Dr. Leonard Sender, medical director of the Children's Hospital of Orange County's cancer program. The two hit it off and soon Babcock was a fixture on the pediatric ward. "In his off-time, he would sneak in to visit with the kids and bring them caps and jerseys," says Sender. "Often celebrities and sports figures do this with cameras in tow because they see it as some sort of photo-op. But not Mike. He would always sneak in with zero fanfare.

"He knows what life is about. Obviously, he has that killer instinct during the game, but he walks away knowing that, ultimately, it is just a game. In my eyes, Mike is a real man."

Babcock makes it clear that, as important as hockey is in his life, it will not be what defines him. "The measure of me as a man isn't going to be how many games I win or how many Cups I bring home," says Babcock. "It will be in the family I raise and the integrity I have in my daily life."

BRINGING THE CUP TO THE KIDS

As in Anaheim, Babcock spends much of his free time in Detroit visiting the kids at the Children's Hospital of Michigan. So much so that hospital officials issued him his own employee ID that says "Coach" to help get him past security guards in case they are among "the one or two people in Detroit who don't know who Mike is," laughs Dr. Herman B. Gray, president of the hospital.

"Mike has been an extraordinary gift to the Children's Hospital and to the community at large," says Gray. "He took a close personal tragedy and made something beautiful out of it."

Babcock donates tickets to every Wings home game for sick kids and their families, meets with them in his office just prior to face-off and makes sure they get the full red-carpet VIP treatment. When the Wings came back home with Stanley Cup in tow, the first place Babcock took it was to the Children's Hospital. "Someone from the Red Wing organization told me that Mike started planning this as soon as they got on the plane in Pittsburgh [after winning]," says Gray. "Needless to say, this was the thrill of a lifetime for many of these kids.

"When he visits the children, he is saying, 'You are important. You are special. I care about you.' That's very powerful, not just for the kids but for all of us. For a mother and father sitting bedside day and night, to see their child smile when smiles are hard to come by, it really is a tremendous gift. Mike is not a warm and fuzzy guy, not a back-slapper. But he is a remarkably caring man."

Some would say a difference-maker.

Neale McDevitt is the editor of the McGill Reporter, McGill's staff/faculty newspaper. A former member of the Canadian Weightlifting Team, Neale is also a fiction writer and the author of One Day Even Trevi Will Crumble, a short story collection that earned the Quebec Writers' Federation's First Book Award in 2003.