Insights (Page 3)

The War Inside

Department of National Defence

Soldiering is a stressful occupation, but many members of the Canadian military are reluctant to seek out help when struggling with some form of mental disorder.

In a national study led by researchers from the McGill-affiliated Douglas Mental Health University Institute, 8,441 soldiers from across the country were surveyed about their mental health. More than 1,200 of these soldiers met the criteria for at least one mental disorder. The most commonly reported problems included depression, alcohol dependence and post-traumatic stress.

But soldiers tend to suffer in silence.

"Our findings show more than half of the military members with a mental disorder do not use any of the mental health services available to them," says lead author Deniz Fikretoglu, a McGill postdoctoral fellow based at the Douglas and an expert on post-traumatic stress disorder.

Many soldiers didn't believe they needed help, or were wary of the military's health and social services agencies.

It's in the military's own interests to make sure that its soldiers are well taken care of, stresses Fikretoglu. "Mental health disorders are associated with high rates of attrition in the military."

Alain Brunet, an assistant professor of psychiatry at McGill and the senior author of the study, says military personnel should be encouraged to seek out help when they need it — especially after serving in war-torn countries. He advises the armed forces to take a careful look at how it tends to the mental health needs of its soldiers with an eye toward "gaining the trust of military members." He also recommends "public education campaigns to de-stigmatize mental health problems."

Researchers from the Université de Montréal, Dalhousie University and the University of Prince Edward Island also worked on the study, which was recently published in the journal Medical Care.

Changing the Look of Malaria

The traditional wisdom on malaria: quick to contract, slow to detect. A new technique, however, promises to change at least part of the malaria rulebook by giving the disease a colourful makeover.

Technicians currently detect malaria in infected blood cells by staining slides of blood smears with giemsa dye, which marks the DNA of the malaria parasites. They then painstakingly examine the stained blood samples under an optical microscope.

The process is laborious and requires a very specific skill set.

A research team led by Paul Wiseman, an associate professor in the Departments of Physics and Chemistry, has developed a faster, more user-friendly technique.

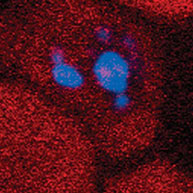

The new method relies on an optical effect called third harmonic generation. THG causes hemozoin, a crystalline substance secreted by the malaria parasite, to glow blue when irradiated by an infrared laser (see image above).

Each year, upwards of 500 million people contract the malaria parasite, and one to three million die from the resulting disease. Most of the fatalities are concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, where diagnosis is stymied by a dearth of trained personnel and equipment.

In their study, published in Biophysical Journal, Wiseman's team argues that their new technique could eliminate the need for specialized training, slides, staining and microscopes — spelling the welcome end of a labour- and time-intensive process. The faster a person is diagnosed with malaria, the faster they can get treatment. Early treatment not only prevents complications, it dramatically reduces the risk of death.

Wiseman and his colleagues now hope to adapt existing technologies, including fibre-optic communications lasers and cell sorting technology, to quickly move the technique from the laboratory to where it's needed most.

"We're imagining a self-contained unit that could be used in clinics in endemic countries," he says. "The operator could inject the cell sample directly into the device, and then it would come up with a count of the total number of existing infected cells without manual intervention."