South Africa's Long Walk Out of History

South Africa's Long Walk Out of History McGill University

User Tools (skip):

South Africa's Long Walk Out of History

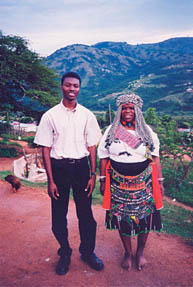

Author Mark Searl with a 'sangoma,' a Zulu traditional healer.

Click to enlarge map

A recent law grad reflects on the year he spent working and touring in South Africa, a country slowly making its way along the difficult path to democracy and opportunity for all its citizens. One observer's view ten years after the collapse of apartheid.

I have finally completed reading Nelson Mandela's riveting autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom. I'm several years late in doing so, as a South African sitting next to me on a domestic airline flight once reminded me.

Still, I'm not so concerned about my timing. During the course of reading Mandela's book I have witnessed the funeral of Walter Sisulu, one of the most respected figures of the anti-apartheid struggle. I have seen Mandela's former home in Orlando West in Soweto, and have visited his Robben Island prison. I have walked the streets of downtown Johannesburg with advocate George Bizos, who represented Mandela (or "Madiba," the clan name by which he is affectionately known in South Africa) and many others during the bleakest years of their imprisonment, and seen the extraordinary manner in which he is greeted by total strangers. From roadside vendors to police officers, people grab and shake his hand or wave from passing cars. In every possible way, my journey through Mandela's autobiography has been animated by the time I have spent here and my exposure to multiple aspects of South Africa's living history.

I came to South Africa in September 2002 as an intern under the Canadian Bar Association's International Internship Program. Conducted in collaboration with the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, the program sends ten young lawyers each year to work for six months with non-governmental organizations in developing countries.

My placement was with the Johannesburg office of the Legal Resources Centre, a public-interest law firm that provides free legal assistance to poor and marginalized individuals. Subsequent to this internship, I participated in a research project on gender and social security reform at the University of the Witwatersrand's Centre for Applied Legal Studies, thereby extending my stay in South Africa to just under one year. Both of these work projects, along with my experiences of living in South Africa, afforded me a healthy glimpse of the fascinating processes that are transforming the country.

It is no stretch to say that South Africa has, like Mandela himself, lived multiple lives within a relatively short period. The nation's stunning metamorphosis from apartheid state to democratic majority rule captured the attention of the world. As it approaches the tenth anniversary of democracy in 2004, South Africa is reaping the benefits of some of the extraordinary changes it has undergone. Bolstered by its own political stability and economic prosperity, the country has assumed a leading role in mediation and peacekeeping efforts in conflict-torn regions of Africa, and is also a key motivator in current initiatives for continental revitalization such as the New Partnership for Africa's Development.

Gandhi Square, a revamped public space that is part of an initiative to rejuvenate downtown Johannesburg.

Mark Searl

Thanks to the country's new constitution and its interpretation by domestic courts, South African jurisprudence is in the novel position of being a point of reference for comparative research on international human rights law. Also, having been readmitted into the international community, South Africa has been aggressively courting international visitors: this is the country that has recently hosted both the World Summit on Sustainable Development and the International Cricket World Cup tournament, and is currently vying (with a good chance of success) to host the 2010 Soccer World Cup. South Africa's striking combination of physical, ecological and cultural splendour is itself no longer a secret, and the country has this year been recognized as the world's fastest growing tourist destination.

My awareness of the "storybook" South Africa has doubtless been a critical element in my forming positive impressions of the country in the past year. I have been no less struck, however, by the extent of struggle and consternation accompanying the successes. To live in South Africa is to be keenly aware of how greatly the present is influenced by the structures of the past, and to constantly wrestle with the reality that true change does not occur overnight.

An 'informal settlement' in Kaserne, a district in Johannesburg not far from the downtown area.

Mark Searl

It is readily apparent that South African society continues to suffer from deep racial divisions. The "rainbow" character of local television and print media advertisements would have you believe that multiracial social circles and close interracial relationships are commonplace; but such mingling is far more the exception than the rule. A visit to Johannesburg's Botanical Gardens in the suburb of Emmarentia reveals South Africa's ethnic diversity in a manner that would not have been possible merely 15 years ago when this area was still classified as whites only.

Upon closer inspection, however, one cannot avoid noticing the frequent homogeneity within the groups that are picnicking, jogging or rowing along the dam: whites with whites, Indians with Indians, blacks with blacks. This division plays itself out endlessly in house parties, restaurants, sporting events, and even universities. It manifests itself in the regularity with which South Africans describe themselves and each other in categorical terms - white people are like this, black people do that.

It is also apparent in the discussions on race-related issues that feature regularly in national discourse: talk shows dealing with affirmative action or land redistribution confirm the significant polarization on these topics between white and non-white communities, and allegations of racial discrimination in any sector attract substantial media attention and invariably spark heated social debate. Confronting the spectre of South African social disunity still touches a very sensitive nerve.

Perhaps more dramatic than South Africa's racial divisions is the severity of its socio-economic inequalities. The country's schizophrenic extremes of affluence and despair suggest that there are in fact two South Africas, each still living in striking isolation from the other.

Saturday mornings in Johannesburg's leafy northern suburbs resemble those of any typically prosperous North American or Euro-pean city, with overflowing sidewalk cafés and shopping malls packed with those stocking up on the week's groceries or the latest fashions and electronics.

Sparkling office towers define the skyline of the Sandton business district and the automotive landscape features a preponderance of BMWs and late- model Volkswagens. There is little in this part of the city to suggest that up to 40% of the country's population of 45 million are unemployed, or that roughly one in every nine persons in South Africa, is infected with HIV. This is the South Africa, which, with its staggering displays of individual wealth and its affinity for the pleasures and comforts of the West, regularly leads newcomers to question whether they are in Africa at all.

Nelson Mandela at the state funeral of African National Congress activist and fellow Robben Island prisoner Walter Sisulu, in May 2003.

AFP / Corbis / MagmaPhoto.com

Meanwhile, barely a half hour away in Soweto, Saturday mornings are characterized by an interminable succession of funeral corteges to the regional cemeteries, several of which have now reached their capacity and are closing.

A weekday visit to township neighbourhoods such as Dube reveals scores of young men strolling the streets or sitting on chairs outside their homes, many of these homes being former hostels built for city labourers under apartheid.

Amidst Soweto's sea of dense housing and corrugated iron shacks, there are many households in which the primary income earner is the grandmother, and the primary source of income is her pension. Indeed, although South Africa stands as an economic giant of the continent and is a magnet for refugees from less wealthy African countries, nearly half of its own citizens are living below the poverty line.

Located between these extremes of north and south, downtown Johannesburg has become a microcosm of the country's racial and socio-economic woes. Many businesses have shut down operations in the city centre and relocated to the northern suburbs, reinforcing the status of these neighbourhoods as enclaves of the minority white population. The city is aggressively trying to attract new capital and promote the major cultural institutions located downtown, but it is hard to mask the damage that mass exodus has already caused. There is still a functioning commercial centre, but the office vacancy rate remains high while the movement of business to the north is growing.

Many South Africans perceive the downtown core to be chaotic, unsafe and out of bounds. The daytime bustle gives way at night to rows of iron-shuttered storefronts. There are no longer lively sidewalk cafŽs on Commissioner or Market Streets, no men in fluorescent gear on President or Plein Streets directing your car to that last parking spot; rather, the dimly lit avenues that are not absolutely desolate are populated with scores of homeless persons, men huddled around fires, and loiterers of every age. The city's dispossessed are overwhelmingly black, whether they be struggling newcomers from rural areas or immigrants from distant countries such as Nigeria and Sudan.

It's funny how with the passage of time, the strange can become familiar. I am now somewhat inured, for example, to the South African preoccupation with security that has been influenced by the high incidence of violent crime. I have grown accustomed to driving through neighbourhoods and seeing high blank walls instead of houses, and to locking an iron gate in addition to the wooden door every time I enter and leave my apartment. It no longer seems so unusual that there are security cameras monitoring the streets in downtown Johannesburg or that my 15-year-old Honda came equipped with an anti-hijack device.

As a black foreigner, however, I have never been able to fully adjust to the segregation of lives and the racially defined disparities in lifestyle that continue to be an inescapable feature of the current face of South Africa. It should not be so predictable that the self-appointed parking attendants who manifest the explosion in the country's "informal" employment sector will generally be black men; nor should it be so inevitable that the nannies and house cleaners who service the homes throughout the suburbs will largely be black women.

South Africa's natural beauty has made it a popular tourist destination. The Amphitheatre in the Northern Drakensburg mountain range is among the most photographed sites in the region.

Mark Searl

Yet these are precisely the scenes that still comprise the South African landscape - repeated at beaches and in boardrooms, at cricket matches and concert halls in which nary a black face is to be found. And by their daily repetition, such scenes nearly succeed in presenting themselves as normal.

What is it, then, that makes this intense environment simultaneously so invigorating? I believe it is the atmosphere of transition itself - an atmosphere reflecting the fact that South Africa, far from being frozen in time, is in the midst of exorcising its demons. It's amazing to read the newspapers here, a country where the state once excelled at monitoring the press, and observe the extent to which the media has become a key watchdog of the state's performance in areas like land reform and black economic empowerment.

Likewise, in a country where the rule of law was once an uncertain refuge for the non-white population, it's enthralling to see civil and social groups such as the Treatment Action Campaign using the language and tools of the constitution to challenge the government's slow and controversial response to the HIV epidemic. The newly enjoyed freedoms of expression and association are being used to focus on the obstacles that continue to prevent a large number of South Africans from living substantially better lives.

The country's problems continue to loom large but with the government under constant scrutiny, real progress is being made in building houses, improving access to water and electricity, and expanding social services. Black, Indian and mixed-race South Africans are penetrating into fields of endeavour from which they were largely excluded before. New forms of artistic expression are emerging, such as Zulu opera and "kwaito" urban music (akin to hip-hop or rap), that constitute a uniquely African re-imagining of existing cultural genres. These are all exciting trends signalling the fact that South Africa is, in the truest sense, a developing country.

During my time here I've found it fascinating to witness a country in vigorous conversation with itself, continually asking the question "Where are we going?" even as it rejoices in the victories already achieved.

The funeral of Walter Sisulu exemplified this mix of optimism and sober reflection so typical of life in contemporary South Africa. Bishop Desmond Tutu in his sermon took stock of the nation's current challenges, noting that Sisulu and South Africans as a whole did not fight for freedom so that they could become slaves to poverty and crime, unemployment and disease. Yet the crowd of thousands at Orlando Stadium that sang throughout the service, laughed at Bishop Tutu's jokes about Mandela and Sisulu, and erupted with glee as Madiba rose from his chair and began to dance to their strains, clearly understood the significance of the moment. Walter Sisulu had earned for South Africans - and South Africans have earned for themselves - the right to celebrate.

South Africa's history over the past decade has borne out the truth of what Nelson Mandela states at the conclusion of his autobiography: that the end of apartheid and the transition to democracy did not in themselves bring freedom, but only the ability to pursue freedom and the beginning of a "longer and even more difficult road." His countrymen are poignantly aware of the fact that they are in many respects still trapped - separated from each other by language, culture and the added baggage of historical circumstance, and kept from realizing their true potential as a nation by the immense knots of the apartheid legacy that must now be painstakingly unravelled.

Thus, the story of the "new South Africa" is no Cinderella-like fairy tale of transformation from one state of affairs to another post-1994, but rather one in which change is being pursued - and with difficulty. How remarkable, though, are the steps that have already been taken on this long walk.