Amal El-Sana builds bridges. So when the young Bedouin Arab saw the distance dividing her goals from her six brothers' wishes she got to work fashioning a span. She explained again why she wanted to leave Israel to study social work in Canada.

While her brothers admired her motives, they remained opposed.

El-Sana, 25, drew up a new plan. She invited a McGill social work professor to spend a day with her family. So on a hot morning last May, Jim Torczyner, a New York-born Jew, arrived in Lagiya, a Bedouin village in the Negev Desert, along with his wife, Jadis, and daughter, Carla.

Here they were greeted by El-Sana's family and friends and ushered into a white concrete and plaster house. They sat on carpets and were offered bowls of fruit and nuts, a large dish of chicken and rice, smaller plates of hummus and eggplant. El-Sana's mother presented them with gifts: handmade olive oil, rich Bedouin embroidery.

Then, after many courtesies and conversations, Torczyner took part in a Bedouin ritual. He promised to look after El-Sana as his daughter in Canada, and the Bedouins would reciprocate whenever Torczyner's daughter came to the Negev.

El-Sana's own "peace-building" opened the way for her to come to McGill. And it reflected her politics and those of the new program: McGill's Middle East Graduate Fellowship in Human Rights, Social Development and Peace Building.

This past year, she and four other fellows have been attending classes to-gether, sharing an office, and learning the practice of social work in Canada. In addition to El-Sana, the group includes two male Jordanian Arab professors -- Mohammad Maani and Hmoud Al-Olimat -- and two female Israeli Jewish graduate students -- Merav Moshe and Noga Porat. In the second year of the fellowship, they'll return to their home countries and apply what they've learned at McGill in community advocacy groups in Jerusalem, in shelters for Jewish and Bedouin women, and in the first school of social work in the Arab world.

Developed by the McGill Consortium for Human Rights Advocacy Training (MCHRAT) and Torczyner, the Middle East fellowship is based on the philosophy that the best hopes for peace in the Middle East rest in "reducing inequality and promoting civil society." Now that the fellows are working together at McGill, Torcyzner thinks the program -- which costs $672,000 for two years and is funded in part by the Canadian International Development Agency, a Swiss foundation, and private donors -- will sell itself. McGill waived tuition for the fellows.

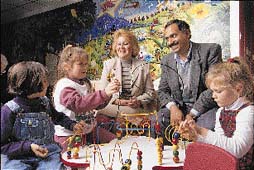

| Hmoud Olimat observing at the Montreal Children's Hospital

Photos: Nicolas Morin |

Israel and Jordan recently signed a peace treaty but the situation is delicate. Will academic programs, like this McGill one, nudge peace along in the Middle East?

Hmoud Olimat, a Jordanian fellow, thinks so. "I think it will help Jordan solve its internal problems. In Jordan, it's important to encourage the private sector and the community to take care of social services -- but we need trained social workers to do that," Olimat says. "Health clinics and social welfare agencies tend to be run by the Ministry of Health, but they might be better organized privately and locally."

The son of a farmer from Zarqa, north of Amman, Olimat is the fifth of eight siblings. His father grew vegetables and wheat, but the family farm suffered as the Zarqa River became polluted. After working on farms as a teenager, Olimat completed a degree in sociology and then a doctorate at Oklahoma State University.

He is now an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Jordan. But in his McGill office, Olimat is just one of the students, a soft-spoken man dressed in flannel trousers and a tweed jacket. He offers a cup of Arabic coffee brewed on a filter machine. A copy of an Arabic newspaper, Asharq Al-Awsat, printed in green ink sits on an adjacent desk. Above him on a filing cabinet are box files of periodicals: Canadian Demographics, Homeless Youth, World Jewish Demographics.

Olimat has come to Montreal with his wife and five children. His particular interest is child welfare, which has led him to fieldwork at the Montreal Chil-dren's Hospital. He attends three social work courses at McGill with the other fellows. A fourth course on life-threatening illness he takes with one other fellow, Mohammad Maani.

Maani is from Amman, the son of a Jordanian civil servant. At home, he is an assistant professor of demography. In Montreal, however, he is visiting institutions that help the elderly. So far, he has been to a Catholic community organization and a Jewish home for the elderly.

"I think the fellowship program will encourage peace, because when you work among people from different cultures, you become more moderate," Maani says. "And the school of social work we want to create (in Jordan) will have professionals who will work among the Jordanian people. They'll help improve their quality of life. And this will bring internal peace, which will serve international peace."

Upon visiting one of the students' seminars, the differences between Israeli and Jordanian political culture are evident. The guest lecturer is law professor Irwin Cotler, BA'61, BCL'64. The topic: human rights. Maani asks Cotler if there is a contradiction between collective and individual rights. He points to a woman's right to have an abortion. How is this right defined? By the society and its religious authorities or the individual?

Cotler cites the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which stipulates that any restrictions on individual rights must be reasonable, demonstrably justifiable, prescribed by law, and consistent with a free and democratic society.

He notes that he was surprised to discover a bloc of African women defending female genital mutilation at an international conference he attended. Customs, he remarks, are often embedded in culture and tradition. Cotler is confronted.

"You're talking and thinking like a man," replies Noga Porat, one of the three Israeli fellows. She goes on to argue that collective rights that restrict women's rights are usually based on patriarchal attitudes.

Torczyner, sitting beside Cotler, then asks Porat what she would say to African women who support genital mutilation. "I would challenge them to see where their views come from," she replies. "From patriarchal attitudes, or free thinking."

Later, the seminar breaks for lunch, vegetarian sushi with hot green wasabe mustard, brought by some of the students. The Jor-danians nibble warily at their first pieces of sushi, then take more.

Back in the office, Porat apologizes for challenging Cotler so bluntly. "Sometimes I put people on the defensive. I need to work on this," she says.

Porat was raised by Orthodox Zionist parents on a kibbutz in the Negev Desert and near Gaza. Later, she renounced her Orthodox Judaism, because of "what it does to women." She went on to command a unit in the Israeli army, become a feminist and worked as a housing activist in Jerusalem. It was there that she met Torczyner.

"Jim is making this big deal about Israeli Jews and Jordanian Arabs working together, but I don't see it that way," Porat says. "I have Palestinian friends and Israelis I can't stand. What matters is what people are as people."

Asked if the fellowship will achieve its aims, she says it is one step in a gradual process. "It's a serious peace-building initiative," she explains. "When you leave peace to governments, you miss the point. It's only when people become active in the process that governments act in their best interests. And I strongly believe people -- Palestinians, Israelis, most people -- want peace."

"Without a vision," Porat says, "it's difficult to change things. I believe Jim has a great vision, and I share this." When she returns to Israel, she hopes to work in housing and collaborate on a project with Amal El-Sana. "Without a vision," Porat says, "it's difficult to change things. I believe Jim has a great vision, and I share this." When she returns to Israel, she hopes to work in housing and collaborate on a project with Amal El-Sana.

El-Sana would like to found a women's shelter with Porat in Beersheva, one that would bring together Jewish and Arab women. She says such a shelter, paradoxically, would be less open to attack.

"Opponents of the shelter will not feel free to attack it. We can protect it by making it for both cultures: that's the paradox.

"Jewish and Bedouin women don't have a place to meet today. Before I knew Jewish women, I had misconceptions about them. But working together, I know their problems. When we are close together, we see our similarities, we can communicate; far apart, we only see our differences."

El-Sana spent her childhood herding sheep and living in houses made of wood and other materials that could be set up and dismantled for easy movement. In high school, however, she wasn't afraid to demand change within her own community. She recruited her girlfriends and sisters and set up the Lagiya Women's Committee to train other Bedouin women to read and write, improve health and prevent family violence. She went on to do a bachelor's of social work degree at Ben Gurion University in Beersheva. Here she took part in demonstrations and benefited from contact with like-minded Israelis. Since her arrival at McGill, El-Sana has visited a Jewish Montreal women's shelter and sat in on meetings of a support group for divorced women at an Italian women's centre.

"I was raised in a traditional society, but I take things from Jewish culture which is open to other ideas, assertive. In our culture, women and men cannot be assertive. Hmoud (Olimat) and Mohammad (Maani) are a bit surprised by how forward [I am]. I learned from the Israelis how to nudge."

As for the fellowship, she says, "I feel this a first step. It's very hard now to make peace in the Middle East. But if we continue now and build in Beersheva, in Haifa, Jerusalem, Amman, this fellowship will help to achieve peace."

How? By developing personal contacts, she says. "Here I feel that Hmoud and Mohammad say to me, 'Amal, you're part of us.' I feel comfortable to communicate with these two groups (Arabs and Jews)."

Like El-Sana, Merav Moshe comes from Ben Gurion University in Beersheva. There, Moshe was director of fieldwork; at McGill, she's doing a joint doctorate in social work and law. Born in Brooklyn and raised in a conservative Jewish family, she visited Israel at 15. After completing a degree in social work in New York, Moshe, at 21, chose to settle in the Negev town of Arad, a new development at the time.

There, she set up a program to help young men in street gangs and later established a drop-in centre for teenagers. She helped create workshops for parents of adolescents and encouraged Israeli youths to form self-help groups to identify common needs. "The idea of the self-help group was very new in Israel: Israelis didn't traditionally talk in groups," Moshe points out. "But I wanted to help communities define their own needs, get those needs met.

"This was a different kind of social work, and when I met Jim at Ben Gurion, I was impressed by his approach, developing partnerships among communities and social workers and government organizers. We were broadening the definition of social worker into community advocacy and human rights work."

She thinks the McGill fellowship is the first of its kind and that it provides a microcosm of Middle East relations.

"On a personal level, it's been easier for Israeli women to establish relationships among ourselves -- we're still getting to know the Jordanians personally. We're finding out how to create trust. At some point, though, we'll ask ourselves and the Jordanians how we can make a difference when we go back to the Middle East. I'll give whatever I have and I'm sure that, reciprocally, the Jordanians will respond. Hmoud has already offered help with statistics for my doctorate. I can go back to Israel and say to my colleagues at Beersheva, 'I've met two wonderful Jordanians,' and I can work to spread that goodwill.

"There's a saying in the Torah that I think of often: 'Life and death are in the power of the tongue.' "

|