|

| |||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

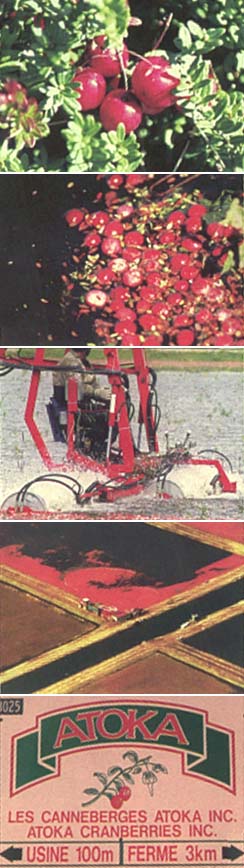

Once upon a time, not so very long ago, cranberries appeared at the dinner table twice yearly: Thanksgiving and Christmas. For the rest of the calendar, they remained forgotten, spurned, overshadowed by sweeter, less gustatorially challenging berries. But no longer. According to the Florida Department of Citrus, cranberry juice is now the third most popular fruit juice (after orange and apple) in Canada and the United States. Canada's Cranberry King, Marc Bieler, DipAgr'58, BA'64, is helping to ensure it stays that way. Fourteen years ago, he planted his first crop on what was generally thought to be agricultural waste land near Saint-Louis-de-Blandford, Quebec. Today, his company, Atoka Cranberries - its name taken from the Abenaki word for the berry - is the largest independent grower in Canada. The Bielers constitute a royal family of cranberries. Marie (Bussières) Bieler, BSc(Agr)'80, Marc's wife, is an agronomist with a speciality in horticulture. Marc's brother Philippe, BEng'55, has a 24 per cent interest in the company, while Jean-François, 25, one of two children Bieler had with his late first wife, works as a project manager. Marie's brother Michel, DipAgr'74, is also involved in the cranberry enterprise, and her family has a history of involvement in agriculture. Her grandfather, Adélard Godbout, was a former Quebec minister of agriculture and Liberal premier from 1939-44, so it was fitting that Marc won the 1996 Adélard-Godbout award given by l'Ordre des agronomes du Québec. "The award is only given to people who don't have degrees in agriculture; I have a diploma, but not a degree. My wife isn't eligible, because she's got an agriculture degree," Bieler chuckles, enjoying the irony.

The Bielers live with their three young children, Guillaume, 5, Raymonde, 4, and Florence, 2 1/2, in a new house on the edge of the cranberry fields that financed its construction. "From the top of the house, Marc can survey all of his lands," jokes brother-in-law Michel. And a wealthy realm it is. Wealthy, because cranberries are a hot commodity, with a market that continues to grow, the robust Bieler explains, lounging in his basement office. The industry is dominated by Ocean Spray, the Massachusetts-based growers' co-op that includes most American and Canadian producers; they generated US$1.4 billion last year, according to company spokesperson Skip Colcord. Their advertising campaigns over the past two decades are responsible for making cranberries familiar to the workaday palate. In 1960, almost all of the cranberry market was in sauces. However, in 1959, rumours (long since disproved) that cranberries could cause cancer put the industry at risk during the fall holiday season, the only time the berries had a market. Ocean Spray decided to develop a year-round market to avoid a recurrence of the near-disaster, and by the mid 1970s half of cranberry sales were in drinks. Today, that number is over 80 per cent. But Ocean Spray was guarding its territory jealously. When Bieler started, the co-op had 85 per cent of the market and wasn't taking on new members. "We had trouble getting financing because the banks would say, 'Well, you're not with Ocean Spray - how are you going to sell?' So early in the game we had to develop a diverse clientele, selling fresh fruit, bulk fruit, sauce, and specialized packages, under our own name and to distributors. This year we're also set up to sell juice to bottlers." While not seriously challenging Ocean Spray, Atoka has claimed a good chunk of the cranberry world as its own. The Atoka empire has grown steadily, but the first steps weren't easy. A cranberry field requires three years to mature to the point where it will yield berries, and five years before it will give the farmer a full crop. At an average start-up cost of $30,000 an acre for engineering, bed preparation and planting, those first thin years eliminate many a farmer who would be king. Bieler knew the game, though. "I was in the apple and maple syrup business in the Eastern townships, producing and processing," he recalls. "I and my partners at the time saw that there was a market for cranberries, and we already knew the agriculture business. We hired some consultants and decided that this was a good area to farm." Bieler's apple background has been an asset in other ways as well; he met Marie while she was managing her parents' apple orchard at Frelighsburg in the Eastern townships. A farm management specialist, Marie was also involved in marketing, but, she observes, "with each additional child, my input has decreased." Plants need the right soil if they are to flourish. Luckily for the Bielers, the right soil for cranberry plants - swamp land - is the wrong soil for almost everything else, so the land is relatively inexpensive and readily available. Cranberries are very site-specific, thriving in acidic soil and sand. Atoka's land was reserved by the Department of Agriculture at the beginning of the century to sell to people who wanted to set up agricultural operations. No one wanted it, though. Nothing but cranberries will grow there. But if you can grow cranberries, you don't need to grow anything else. While the discreet Bielers will not say exactly what the profit margins are, cranberry people in general note that theirs is perhaps the biggest money-maker of any crop, barring the illegal marijuana industry. The American market consumes 65 per cent of the Bielers' product, while 27 per cent is sold in Quebec, five per cent in the rest of Canada, and three per cent in Europe. This year, Bieler's farm produced 3.7 million pounds for happy gourmets. "Cranberries like a northern climate," Bieler observes, grinning. "This area has optimal weather conditions," he continues, happy in the knowledge that few farmers can say the same of Quebec. Bieler's region is one of the prime growing areas in Canada, along with the Vancouver suburb of Richmond, home to many Ocean Spray growers. The berries also suit the Canadian economy because they aren't particularly labour-intensive, meaning Canadian growers do not have to compete with lower labour prices abroad. Instead, berry-growing is high-tech, requiring sophisticated methods to control water levels for irrigation and flooding. Atoka has a 100-hectare reservoir which is drawn upon to frost-proof the plants in the spring, water them in the summer, and flood the farm's 420 - and growing - acres during the harvest and over the winter. The reservoir, an important feature of any cranberry farm, also provides a home and buffet for many animals; American studies show an increase in fauna around cranberry plantations, and Atoka has its share of resident otters and waterfowl, as well as transient moose. Being the Cranberry King is a year-round job. After harvest, the beds, which are really pits several feet deep, are flooded to protect the plants from the cold. Over winter, sand is layered on the ice and snow above the dormant beds; come the thaw, the sand drops beneath the plants, renewing the beds so that with proper maintenance they can produce a healthy crop annually. Easy enough: but the real work begins in the spring. New beds - five-acre rectangular pits, 50m by 500m, that are prepared in autumn - are planted in May. Meanwhile, the crop which has emerged from under the layers of winter snow is kept under a constant spray of water to protect it from frost. Plants are fertilized in June, and sprout small pinkish-white flowers in July. At this point, the Bielers go to local apiaries to hire three hundred hives of bees to pollinate the flowers. Alas, Jean-François notes, "cranberry honey doesn't taste good, so we don't market it." As the growing season progresses, more fertilizers are added, along with herbicides for the newer beds (which are susceptible to weeds) and pesticides. In September the fields are crimson, and excursions through the berry beds, offered throughout October by the Centre d'Interprétation de la Canneberge, entice curious tourists. The Bielers, though, do not have the luxury of admiring the autumnal hues. Harvest coincides with Canadian Thanksgiving, the start of the big market rush for the fresh berries. Atoka's workforce, which normally ranges from fifteen to twenty-five people, swells to forty. The double task of getting the berries from the fields and to the market is exhausting. "During harvest," recalls Jean-François, "I worked fourteen to sixteen hours every day, mostly at the factory, and I was dreaming of cranberries - for six weeks!" Berries that aren't sold or processed immediately go into freezers in nearby Quebec City, and are trucked to the factory for juicing. The Cranberry King is pushing Atoka's boundaries further each season. As he strides across bulldozed land to plant flags marking the sites of new beds, Bieler radiates enthusiasm. "It's technically quite demanding," he observes happily. Notes Jean-François, "My father loves expanding the business, maybe even more than growing berries." New land is being prepared for berry beds; the factory, just off the Trans-Canada highway, originally used to sort berries for the fresh-berry market, has grown to include climate-controlled storage space and a sauce-maker. Last year, a juicer - massive vats that clean, mulch and filter the berries - was added, so Atoka can process its own berries. The juice is sold to bottlers, such as the Metro chain of stores in Quebec, who then water it down (cranberry juice is too bitter to be palatable unalloyed), bottle it, and affix their own labels. Atoka itself markets sauces and fresh berries in Quebec, and last December sent over 120,000 pounds of cranberries tumbling onto the Christmas market. With all those berries around, you might think that the Bielers would be bored with them. Not so, however. Marie has become an expert in "cranberry applications," developing a myriad ways one can eat the berries. As she points out, "You know cranberries have hit the mainstream when Jell-O has them as a flavour." A tart red punch makes its way to the dinner table regularly; cranberry mousse is served up for dessert. And when the Bielers, Canada's royal family of cranberries, gather around the table, cranberries cease to be a business, becoming instead what they are for others: a taste. | ||||

|

| |||