|

| ||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

by Jean Benoît Nadeau, BA'92 photos by Nicolas Morin | |||

| |||

|

I became a self-employed journalist one morning in January, 1987. It was -20 C, and I was 22 years old. I standing on a reservoir in an east-end Montreal refinery, measuring the oil level with a weighted chain. I had arrived there three months earlier after studying a range of topics: civil engineering, literature, dramatic writing. But this January morning, I suddenly roused myself from that long mental malady known as adolescence. I decided that I would become a journalist and that I would finish my studies in political science at McGill. I didn't doubt that I would access, at the same instant, the world of the self-employed worker. In fact, I became a self-employed worker twice: the first time by necessity, the second by choice. Employers weren't clamouring to take on an aspiring but unproven journalist such as myself. For three years, I would place an article here, an article there, all while finishing my studies. Eventually, magazines offered to hire me, and I refused. That's when I became self-employed by choice. At the start of my freelancer career, I complained bitterly that I would never find another job. My father, an associate in an engineering firm, surprised me one day: "But that's very good, my son." He always called me "son." "There are many fiscal advantages to being self-employed." I learned that I belonged to a category of honorable individuals, though hybrids: part person, part enterprise. This episode took place towards the end of the 1980s. There were then several tens of thousands of self-employed workers -- farmers, professionals, artists, craftspeople -- who would never label themselves as such. Ten years later, a legion of the ex-employed, ex-executives, apprentices, CEGEP and university degree-holders -- released from work -- were thrown to their own resources, by choice or by obligation. Quebec counts 500,000 self-employed works, almost 15 percent of the active population, 100,000 more than the civil servants and the unemployed. A half-million people muddling through! But precisely what is a self-employed worker? The defeatist's definition: a poor soul without a job who barely manages to earn a living. Those who think like this are travelling the wrong road. They will work for nothing for the first client to come along, in the hopes of getting a job. The poor sap who lives through purgatory awaiting the safety of a job is condemned to a life of precariousness thanks to this bad attitude. My definition, inspired by Yvon Deschamps' famous line "My mother has no job - she has too much work," is more affirmative. A good self-employed worker:

Work. The idea may seem incredible for a died-in-the-wool employee, but know-how is very profitable, thanks to the laws of supply and demand. If you are competent and useful, you will always have plenty of work -- perhaps even enough to consider hiring someone. Clients. Contrary to the old adage, the customer isn't always right. In fact, the client is often wrong, particularly when the time comes to negotiate. From a business point of view, it's an equal relationship. Ideally, you will have many. Revenue. The self-employed worker doesn't touch a salary, but rather has a revenue, invoicing clients bills with taxes included. Anyway, you can put yourself on salary if you think the GST is a nuisance. The first difficulty in becoming a self-employed worker is perceptual. You are researcher, sales-person, chief negotiator, director of accounts-receivable, financial comptroller, accountant, president and CEO, president of the board of directors, and public relations officer. And also secretary to the above! In short, you are the entire enterprise. A self-employed worker who speaks of "jobs," "bosses," and "salaries" understands nothing. He suffers because he doesn't see himself as an enterprise.

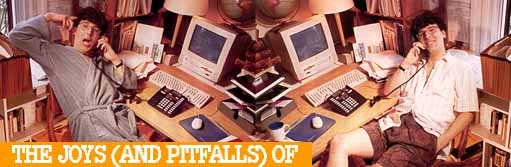

It can be difficult to leave behind those employee reflexes. We all have the idea that a job is the goal of life. It plays such a major role that we mirror it to our children: "Study if you want a job," we tell them. The boss-less, if not himself an employer or a professional, is corrupt, a delinquent. However, idealizing the salaried class is a recent phenomenon. It is impossible to date the arrival of the first self-employed worker on the scene for the good and simple reason that people have always been self-employed. It is the human condition. Autonomous workers aren't only those found in history books (Christopher Columbus, for instance). Farmers, vendors, craftspeople, soldiers: they weave a thread through the centuries. It's an error to believe that prostitution is the oldest profession. Until recently, no-one wished to draw a salary. The condition bordered on slavery and derived from one's inability to be a farmer. As one could not divide farmland into tiny pieces for 14 children, one child took the land, and the rest placed themselves at his service. The slave is the ultimate employee, assured only of subsistence and belonging by rights totally to the employer. Free, the farmer or the craftsman -- scribe, cobbler, blacksmith -- owned his own means of production, his skills, indeed his own slaves. Employment, such as we understand the term today -- marked by status, protected by law, coveted and desirable -- belonged to an elite group of servants jealous of their privileges. They were numerous in Ancient Rome, in Egypt (scribes) and in the church, the first multinational corporation to offer job security until the end of your days, and paradise until the Last Judgement. But today's notion of a job is very new. At the beginning of the 19th century, the industrial revolution provoked unprecedented changes in the non-farming population (which is where employees came from), reducing people to poverty and misery. For political rather than humanitarian reasons, some individuals acquired rights, such as the right to vote and to run for office. Henry Ford was one of the first industrialists to understand that if he didn't share the wealth with his employees (in the form of high salaries), there would be revolution. The history of the 20th century is characterized by governments and companies buying political and economic stability by protecting jobs. The present job crisis is really only one swing of the pendulum. Machines are more efficient that ever. The state has money for neither bread nor circuses. And financiers no longer invest in their own country but instead create jobs elsewhere, where labour costs are lower. Employees here live precariously. Only by striking off on their own can people assure themselves of subsistence and security. And one recalls the oldest trade in the world... The first description of the lifestyle of self-employed workers comes from Xenophon, the citizen, soldier, philosopher and mercenary from ancient Greece who lived between 425 and 355 BC. His Economics, mediated by the figure of Socrates, features the cynic Kritoboulos and the sympathetic Isomachos in a philosophical exchange. The title is very badly translated and quite dramatically misrepresents the subject. In Greek, the work "oikonomikon" signifies "household management." Xenophon's Economics is about the management of agricultural endeavours -- remember: the farmer is a self-employed worker! -- but especially on the manner in which a good citizen ensures his own subsistence, along with a surplus for the state. Simply replace the word "citizen" with "self-employed worker" and the old book is rejuvenated. Xenophon, using Socrates as his mouthpiece, emphasizes the moral virtues of citizens (read "self-employed workers") and their freedom, although that latter term has been much abused these days. I'm always amused when people idealise the freedom I have as a self-employed worker. Sure, I'm free. I can work in my bathrobe until noon or interview a minister by phone while naked if it pleases me. And I have no boss to scold me if I take off for an afternoon... ...But if I take it easy every day, I won't last long. Freedom comes with burdens: I am responsible for myself, for my security, for my professional sabbaticals, for my holidays, for my time. My money doesn't parade in jauntily each week or each month, but comes in more or less substantial packs -- usually "less" rather than "more." When it comes to borrowing money to buy a car, I am shunned by the friendliest banker. My office is close to the box. My cat, motivated by the purest sadistic impulses, mutilated the last fax of my interview with the minister. And potential clients inevitably call me just when the baby begins to bawl. Is this how I attain my freedom? The problem is badly phrased. To me, you are free two or three times in your life, when you make a profound decision regarding studies, work, love.... After making that decision, you assume the consequences and try to organize everything so that you will have the elbow room to respond the next time you have to make a major decision. That's freedom for you. So, are you cut out for the freelancer's life? This time, lets go right back to Socrates 101 and his famous maxim "know thyself." To succeed, you need talent, time, judgement, and the ability to work alone and develop some important character traits. An aspiring jockey who is 2 meters tall and weighs 100 kg is more cut out to be a horse. You simply cannot get past physical constraints (time and money, for instance), as well as other barriers of talent or personal taste. Public relations in the pharmaceutical industry is lucrative, but if you hate biology and are honest about it, you won't go far. You can address the question of qualifications if you have the time (and the money) to acquire them. But if you have no-one to support you - financially and morally -- for the year or two of your apprenticeship, think again. You can try to land your first big client before quitting your job -- although this is unlikely -- or dig up a part time job to keep your bread buttered during your apprenticeship. Besides, why shouldn't a little time be necessary? Engineering students live in slavery: studying for five years, then working at partial salary for another two. Are they oppressed? No. Society insists upon having airplanes that won't crash and bridges that won't collapse. And no-one cries when a student bombs on an exam. Why should it be any different for a self-employed worker who has to provide a good or service for demanding clients? You can live well as a self-employed worker, even though it isn't like striking gold in the Klondike. At the start, your ambition must be to make a decent income, and, before anything else, to do that which you love. You won't be taking champagne baths for the first few years. When I began, the cultural weekly Voir paid me $20 a page and I was very proud to have made something extra to finance my studies. I earned $2000 in my first eight months as a freelancer. Two thousand dollars! It was ridiculous, but I also learned much and that was essential. Naturally, a self-employed worker who masters his area will make much more the first year, assuming that time is taken to prepare herself properly. Apart from time and talent, you need the ability to think and work alone. Contrary to life at school or as an employee, no-one will be there to assess your work. Life, the market, and public opinion will judge you; no-one else will establish any standards of evaluation. You won't have a supervisor to organize you and to tell you what to do; nor will you have a superior to go after reluctant payers. Solutions won't be found in the office down the hall. During your coffee break, you'll be alone with your thoughts. Over time, you will develop certain qualities. Consider them analogous to the five scout virtues. The first three are self-evident. You need patience (to pursue the game), audacity (to push hard when the time comes), and curiosity (to stay interested). The other two, honesty and modesty, are a bit more difficult to understand. Honesty denotes candour in your relationships, not the unjustifiable thoughts that you may harbour regarding taxes or clients. You are mistaken if you think that being in business means being a shark. Those who believe that all their clients and their rivals are trying to conquer them are toast. While clients expect to have a clear schedule for the projects, they also want to know about your difficulties. You don't understand the order? You're afraid that you can't make the deadline? Tell them. You will not last long if, lacking honesty, you develop a siege mentality. You will find modesty extremely useful if you don't have all the other virtues. This misunderstood quality doesn't describe submission or servility, though. Mother Theresa is capable of amassing millions of dollars for her cause, but that doesn't stop her from being humble. There is no contradiction between humility and the capacity to sell yourself. Modesty comes with the job. The apprenticeship is always longer than expected. Before accusing others, consider if perhaps you have misunderstood or badly negotiated, defined or executed the job. The indignant reflexes of a Miss Piggy are counter-productive. For a journalist, the worst thing to say is "I don't need to be corrected, I'm an award-winning writer." You will lose with this attitude, unless you're the reincarnation of Victor Hugo. Not making as if you are a genius -- that's modesty -- won't stop you from proving that your ideas are good if you have the ability to demonstrate that you are one. Humility requires acceptance of your abilities. Self-employed workers who always blame others for their difficulties don't go far, simply because they don't understand their new role. If you find the bosses are unfair, too bad. You are, unfortunately, obliged to include yourself in their number. From Le Guide du travailleur autonome, by Jean Benoît Nadeau, published by Éditions Québec/Amérique. Abridged by the author. | |||