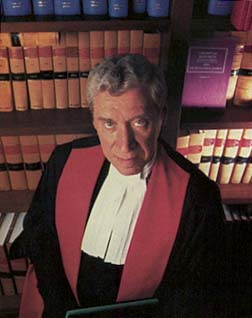

The Honourable Mr. Justice Charles Gonthier, BCL'51, LLD'90, the Supreme Court of Canada

Charles Joseph Doherty Gonthier was named to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1989. A native of Montreal, he attended Collège Stanislas, and the McGill Faculty of Law. Justice Gonthier practised law before being named to the Quebec Superior Court where he is known for hearing the case of French architect Roger Taillibert, who designed the '76 Olympic site and sued the City of Montreal for his design fees. Justice Gonthier personally climbed atop the stadium for inspection; Taillibert received substantially less than requested. Later, Charles Gonthier caught the eye of Supreme Court Justice Brian Dickson who recommended his appointment to the Supreme Court. Justice Gonthier is married with five sons and still finds time to serve on the editorial board of the McGill Law Journal, and to advise the student editors.

One of the most pressing issues currently facing the Supreme Court is the interpretation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In writing the dissenting opinion in Miron vs. Trudel, Justice Gonthier, 68, says he took his "first stab" at writing on the issue of equality rights. The Miron-Trudel case is very important in defining the word "spouse", which appears in many Canadian statutes. |

Supreme Court Judge Charles Gonthier at his Sussex Street office in Ottawa

Definition of "Spouse"

Miron vs. Trudel (1994)

The case: John Miron and Jocelyne Vallière lived together in a common-law relationship for 11 years with their two children. When John was injured in a car accident, he made a claim against Jocelyne's insurance, which extended benefits to her "spouse". The claim was denied by the insurance company because John was not considered to be a legal spouse. The Ontario Court of Appeal dismissed the claim that the Insurance Act was discriminatory under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Supreme Court considered the discrimination and voted 4-3 in favour of the couple.

Charles Gonthier wrote the dissenting opinion: "An additional element distinguishing marriage is the permanence accepted by the parties to the marriage contract."

Justice Gonthier had to decide whether unmarried people were discriminated against under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. He used the three tests of discrimination: whether there was a distinction between unmarried people and others, whether unmarried people were disadvantaged, and whether being unmarried was a personal characteristic akin to a racial or gender characteristic.

"The question raised by the case at bar is intimately linked with the institution of marriage, the importance of which has long been recognized in our society." Gonthier stressed the integrity of the marriage contract and its "bundle of benefits and burdens" including the obligation for mutual support. "In my view, freedom of choice and the contractual nature of marriage are crucial to understanding why distinctions premised on marital status are not necessarily discriminatory: Where individuals choose not to marry, it would undermine the choice they have made if the state were to impose upon them the very same burdens and benefits which it imposes on married persons."

In writing the majority opinion, Justice Beverly McLachlin argued, "Historically, in our society, the unmarried partner has been regarded as less worthy than the married partner. In theory the individual is free to marry", she wrote, "but not in practice, due to the law, the reluctance of one's partner to marry, or financial, social, or religious constraints."

Justice Gonthier, however, cautioned that "the courts must be wary of second guessing legislative social policy choices relating to the status, rights and obligations of marriage, a basic institution of our society intimately related to its fundamental values." |

Daniel H. Tingley in front of Chancellor Day Hall, the McGill Faculty of Law

PHOTO: SPYROS BOURBOULIS

A Promise Made and Accepted

The mistress vs. the estate of her married Westmount lover (1993)

(Note: While the 1993 case is on public record, names have been omitted as the parties still live in Montreal.)

The case: During the last 19 years of his life, a Montreal shipping executive, "Mr. Z," maintained two lives, a public one with his wife and a private one with his mistress. When he died, he left everything to his wife and made no mention of his mistress. The wife first learned of the other woman when, following the memorial service, her husband's longtime accountant asked her if she knew of the "other house". The other house was on Roslyn Avenue, less than 2 kilometres away from her Mount Pleasant home in Westmount.

At the hearing, the mistress told of living in and running the Montpetit St. apartment building which was bought by Mr. Z's incorporated firm. Once a television performer, the mistress stopped working to make herself more available for Mr. Z. The Montpetit apartment was sold and the firm bought the Roslyn Avenue house where the mistress lived rent free. Mr. Z. also paid his mistress $18,000 per year. Before his death, he instructed his accountant to wind up the firm and to give part of the Roslyn property sale proceeds to the "present tenant". The mistress claimed that Mr. Z. planned to give her the proceeds from the gain on the sale of the Montpetit property for her services as manager. He gave her a cheque for the amount but cautioned her there were insufficient funds to cash it at that moment. She photocopied the cheque and returned it.

Judge Tingley conceded, "There is no basis in our civil law to enforce or sanction a mere promise." He added, "Our Courts will, however, sanction a promise that has been accepted for that is at the heart of the formation of a contract." Judge Tingley decided that the mistress should be compensated based on three events: the purchase of the Roslyn property, the giving of the cheque, and Mr. Z's final instructions to his accountant. "He did not want his wife to know of his private life yet he did want to honour his commitment to (mistress's name)," wrote Judge Tingley. The mistress was awarded $162,450 for the gain on the sales of the Montpetit and Roslyn properties. The case is under appeal.

Celliers du Monde Inc. vs. La Société des Alcools du Québec (SAQ) (1996)

It was 8 pm on a Friday night last summer when Dan Tingley was asked to hear an urgent case. Two bottles of wine were plunked in front of him. "Are these for me?" asked the hopeful judge. Alas, they were not. They were evidence. The local distributors of "Le Caballero de Chile, Cosecha Reservada" Chilean wine asked Judge Tingley to order the SAQ to reinstate distribution throughout Quebec. The SAQ, a Quebec government-owned monopoly, argued that the words "Cosecha Reservada" on the promotional collar were not translated into French and thus violated Quebec language laws. Judge Tingley saw that the translation "Cuvée Réserve" appeared on the front label. He heard that the $9 wine had won an award as the best in its class, and the promotional label was added to publicize that fact.

"By the time I understood the problem," said Judge Tingley, "I was both thirsty and angry. I told the SAQ lawyers that it was not their client's business to decide on matters of language, but to deliver quality wine. The SAQ operates a virtual monopoly in the distribution of wine to convenience stores in Quebec. Its refusal was tantamount to keeping the competition out." He ordered the SAQ to deliver the Caballero wine with the collars. The judge left empty-handed that night, but was able to purchase the Caballero wine the following Monday. The parties later settled out of court.

| The Honourable Mr. Justice Daniel H. Tingley, BA'63, BCL'63, Quebec Superior Court

A partner in the Montreal firm of Lafleur, Brown, Dan Tingley was appointed to the Quebec Superior Court in 1992. Born in Winnipeg, Judge Tingley alleges that his admission to McGill Law School was linked to skills other than academic. (read: football). Accordingly, he has advocated that McGill's admissions process look beyond marks. "It was a shame. We were losing adventurous students to Queen's and to other universities," Tingley says. For a number of years, McGill has given special consideration to students who did high school in a second language.

A longtime Graduates' Society board member, Judge Tingley, 58, has taught business organization at McGill and libel law at Concordia. He is a member of the McGill Board of Governors.

|

The Honourable Mr. Justice Benjamin J. Greenberg, BA'54, BCL'57, Quebec Superior Court

Benjamin J. Greenberg was a top law student at McGill. He won the Elizabeth Torrance Gold Medal, given for the highest standing in his graduating class, and the Macdonald Travelling Scholarship, which he used to study law at the Sorbonne. He also won the IME Prize for commerical law, the Montreal Bar Association prizes in civil law and civil procedure and the Greenshields Prize for criminal law. Married with three children, Justice Greenberg practised corporate and commercial law in Montreal and was active in the Jewish community. In 1976, he was appointed to the Quebec Superior Court. Last year, at 62, he was "Judge in Residence" at the McGill Faculty of Law, as part of the new National Judicial Study Leave Fellowship Program. He studied Charter law, gave several lectures and coached McGill students in the competitive mooting programs. Justice Greenberg plans to retire at 65, then pursue the growing field of alternative dispute resolution. |

Benjamin J. Greenberg in his office at the Palais de Justice

PHOTO: SPYROS BOURBOULIS

|

The Oka Case

Her Majesty the Queen vs. Ronald Cross and Gordon Lazore

The case: When the Municipal Council of the Village of Oka, Quebec, proposed enlarging the Oka golf course in 1990, the Mohawks rose in defiance. They had unsuccessfully opposed the golf course 30 years ago and now feared disturbance of "the Pines" and the ancient Mohawk cemetery. (In the Sentence, Judge Greenberg presented a thorough history of Mohawk claims on the land, and its special spiritual and cultural importance.) The Mohawks of Kanehsatake erected a barricade which one judge ordered removed. Negotiations between the Mohawks and the Government of Quebec were interrupted by a Sûreté du Québec (Quebec provincial police) raid which led to violence, the death of one officer, and barricades, including one which blocked the Mercier Bridge, preventing many Montrealers from getting to work. The judge noted that although Ronald Cross, known as "Lasagna" in the media, and Gordon Lazore, known as "Noriega," were charged with 59 counts, many others were involved.

The first set of counts was for violence against fellow Mohawks Francis Jacobs and Ronald Bonspille, who organized house patrols at Oka to deter thefts in the area blocked off by Mohawk barricades. Cross believed that Jacobs had called in the media to televise his motorbike being tossed off a truck and set aflame. He and five others beat Jacobs and his son Cory with a baseball bat and destroyed their car. The group then traveled to Bonspille's house where they destroyed a Kahnesatake ambulance parked out front. Bonspille's son had fled the house in his underwear and hid in the bushes nearby.

Justice Greenberg wrote, "In respect of the Jacobs and Bonspille incidents, the victims being fellow Mohawks, the comments which I made concerning the mistreatment over the years of the native peoples by the wider society can play no mitigating role whatsoever." The second set of charges dealt with conflicts with the Canadian army.

The court heard that Lazore, 32, was a high school graduate with a fairly constant work history. One of five children, he lived at home and took care of his 75-year-old handicapped mother. Lazore had a criminal record for possession of illegal tobacco products.

Cross, 34, was also a high school graduate, whose father drowned in 1967. One of seven children, he is married and has a son, born during the trial. Greenberg wrote, "Lasagna's public image was purely a creation of the media" and that there was no evidence he led the Warrior Society. "I am satisfied that he was not motivated by greed or reasons of personal gain. He acted out of a deep anger, rage, desperation and sense of hopelessness, all the result of systematic discrimination and racism against his people over several centuries."

"It is now my duty to impose Sentence. In my view, that duty is manifestly the most difficult and delicate one which a judge can be called upon to perform." Greenberg decided some sentences would be served concurrently. Cross received 52 months of imprisonment and Lazore received 23 months. Both were ordered not to possess firearms.

"Perhaps the irony will not be lost on the accused and their counsel. After the bitter struggle which they waged last April (in this case) on the language issue and the question of whether or not the Crown prosecutors had the right to use French in this trial, it was the contradictory French version of Section 85(2) which saved each of the accused from at least one more consecutive year of imprisonment!" That section provided for the serving of an additional sentence consecutively when a firearm was used while committing another offence.

"I cannot close the present chapter of this Sentence without also mentioning the many tens of millions of dollars which this entire episode has cost the Government of the Province of Quebec, and hence, its taxpayers, you and me!"

The Barnabé Case

Sa Majesté La Reine vs. Pierre Bergeron, André Lapointe, Michel Vadeboncoeur, Louis Samson (1995)

The case: At 3:30 am on December 14, 1993, Montreal taxi driver Richard Barnabé went to talk to his priest at l'Église des Saints-Martyrs canadiens in northeast Montreal. He was extremely upset that his wife wouldn't let him see his son during the Christmas holidays. The priest wasn't there and Barnabé kicked in a church window while shouting hysterically. A neighour heard the commotion and called 911. When police arrived Barnabé bolted and led several police cars on a 10-km high speed chase through red lights and stop signs, ending in the driveway of his brother's home in Laval. (His brother, a police sergeant, did not come out.) During that chase, Barnabé attempted to run down officer Lapointe after his vehicle and two pursuing police cars temporarily stopped in a dead-end street. In his brother's driveway, Barnabé refused to submit to arrest, yelling: "Tirez-moi, tuez-moi." ("Shoot me, kill me"). He also spoke of Satan, Hitler and the Mafia. Once in the back of the police car, he banged his head and feet against the plexiglass partition. After arriving at Police Station 44, an ambulance was called but Barnabé refused help; the two ambulance attendants believed he was intoxicated or psychotic, and called for more help (Later, no alcohol was found in his blood).When assistance arrived, Barnabé had been very forcibly restrained by police in his cell and was in a coma suffering from 13 injuries including a broken nose, a cracked cheekbone, roadburns to his knees, and broken ribs. Five officers were charged, four men and one woman. After eight days of deliberation following a three-month trial, the jury acquitted the woman and found the four men guilty of assault causing bodily harm.

In his sentencing, Justice Greenberg noted that the court could not improve the situation of the victim and that it was not the purpose of the court to be vengeful but rather, to dispense justice. He found the police officers trained in an outdated and dangerous restraint style, that is, holding a person face down on the ground which can lead to heart attack and asphyxia. Justice Greenberg cited medical evidence of Barnabé's paranoid aggressive state and the medical testimony about whether some of the injuries were self-inflicted. The officers, Justice Greenberg noted, had no prior criminal records. Bergeron, Lapointe and Samson were given prison sentences to be served on weekends while Michel Vadeboncoeur got a two-year probation and was ordered to perform community service in a long-term care hospital.

In submitting this case to the McGill News, Judge Greenberg commented, "Most people felt the sentences were lenient but they don't know the facts of the case. There was no evidence of external blows [to Richard Barnabé]." He feels that the media misreported the case, especially the English media, as epitomized in The Gazette's powerful headline, "Beating liquifies brain." The case was heard and written in French. Taxi driver Richard Barnabé died during the summer of 1996.

|

Asylum and Homosexuality (1996)

The case: An Honduran woman facing deportation from the United States asked for asylum. The defendant testified that she feared persecution because she was a lesbian. She said at age 12 she ran into trouble at school for forcibly kissing another girl, then had trouble at home and left at 13. At 15, she had a relationship with a girl whose brother threatened her and told her he'd teach her "what a real man was like." About three weeks later, she said she was abducted and raped by four men, but did not report the incident to police. She moved to Guatemala where she was threatened, and to Mexico where she supervised male construction workers. The defendant said she was beaten up by one worker who said "gay people cannot be bossing Mexicans around." She returned to Honduras for six incident-free months, then came to the United States.

Judge Torreh-Bayouth considered the criteria for asylum based on persecution. "First, was the respondent persecuted on account of her membership in a particular social group; second, was this persecution by the government or by a group which the government is unwilling to control; third, is this persecution country-wide; and fourth, would it allow for granting asylum on the basis of past persecution even if it's shown that there is no well-founded fear of persecution upon return?

"In sum, the respondent had a complex burden in this case. She had to demonstrate not only that she was raped and that she was a lesbian, but also that she was raped because she was a lesbian, that this was done by a person or group whom Honduras is unwilling or unable to stop, and that her fear of persecution would be countrywide."

Judge Torreh-Bayouth decided that the defendant did not meet her burden of proof. Instead of forcible deportation, however, the judge decided the Honduran woman qualified under the Immigration and Nationality Act for voluntary departure contingent on "good moral character for at least the last five years." Judge Torreh Bayouth gave the defendant six months to voluntarily leave the United States in order "to prepare herself emotionally and financially."

|