The return of students to the wide and sheltered steps of the Redpath Museum is one of the sure signs of spring on campus. On sunny days, the museum's entrance has for decades been a popular spot to schmooze or study, to doze or daydream. But the students who gather outside seldom venture in, and so never learn of the fascinating natural history and ethnology collections that lie just a few feet away. Among the Redpath's treasures are whale and dinosaur skeletons, fossils from the Burgess Shale, the bones of a dodo bird, three human and several animal mummies (part of the second-largest collection of Egyptian antiquities in Canada), and an important holding of Greek and Roman coins.

Opened in 1882, the Redpath Museum was a gift to McGill from sugar baron Peter Redpath. Announcing his plans for the project in 1880, Redpath intended the building as a tribute on the 25th anniversary of William Dawson's tenure as principal of McGill. It was Dawson who, with phenomenal energy, commitment and organizational skills, had transformed a scruffy, failing school with an enrolment of 70 into a respected academic institution.

Arriving in Montreal from Nova Scotia, Dawson's first sight of McGill must have been a source of considerable dismay. He wrote that the campus consisted of "two blocks of unfinished and partly ruinous buildings, standing amid a wilderness of excavators' and masons' rubbish, overgrown with weeds and bushes." He moved his family into the east wing of the Arts Building, clearing out the rubble and chasing out the rats, then set about building McGill's reputation. In doing so, he earned the respect -- and financial support -- of the local community.

The inaugural event at the Redpath was a prestigious one. Dawson, a highly regarded scientist himself, had persuaded the American Association for the Advancement of Science to meet in Montreal and a reception was held in the museum's grand gallery for 2,000 people. According to glowing newspaper reports, the crowd included the "principal scientific lights of the nineteenth century" as well as the "elite of Canadian Society."

Museums are notoriously costly institutions to maintain, however, and despite its glorious opening, the Redpath has struggled in this century to fulfil its dual mandate to serve as a research facility for scholars and to advance scientific literacy by offering access to the public. The need for office and storage space has reduced the area available for exhibits. Periodic budget cuts have forced the museum to close to visitors, sometimes for years. Expanded holdings have necessitated moves -- important plant and insect collections were transferred to Macdonald Campus in the 1960s and 1970s, for example.

But thanks to cooperation among departments and the dedication and adaptability of its curators, the Redpath and its wonders have survived. Join us on a photographic tour...

| Greek tetradrachm coin from 474-450 BC, showing the head of Arethusa.

|

|

| 19th century Chinese shoes, including satin slippers worn by women with bound feet, a practice which originated around 900 AD.

|

| "Old George," a silverback mountain gorilla from eastern Zaire, was brought back from the McGill-Congo expedition of 1938.

|

|

| William Dawson's geology class in a limestone quarry in Montreal, circa 1891. Dawson, front row, centre, was in his seventies when the photo was taken. He was still Principal of McGill, and still actively teaching, researching and running the museum.

|

| A view from the upper gallery, showing the original layout of exhibition cases. The side areas have since been walled off to create staff offices and storage space for artifacts not on display. The large skeleton is a cast of the British Museum's Megatherium, a giant ground sloth from the Pleistocene era.

|

|

| Among the extensive collections of artifacts from Africa, Oceania and South America are these African ceremonial knives. Many were made by Kuba artisans from the Congo region out of locally smelted iron.

|

| Male figure with bowl from the Congo collected by McGill professor J.L. Todd, BA1898, MDCM1900, while on one of the first medical expeditions investigating sleeping sickness in central Africa. The background photo is from ethnographer Emil Torday's1925 book, On the Trail of the Bushongo.

|

|

| Kongo figure from Angola, made of wood, metal, glass, bone and cloth. Originally donated to the Natural History Society of Montreal in about 1860, it came to the Redpath Museum when the society disbanded in 1925. Figures of this kind were considered to be very powerful and were kept in the community to protect its members.

|

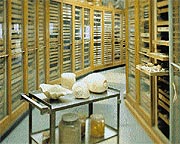

| The Redpath has roughly 30,000 lots of molluscs, which include the Carpenter Collection (donated 1867, international in scope), the Mickles-Conde Collection (donated 1948, mainly Caribbean and Florida), a Dawson collection (mainly eastern Canada) and the Levine Collection (donated 1995, worldwide). Among the corals are specimens from all over the world with an emphasis on Caribbean species.

|

|

| The museum has over 1,600 lots of fish specimens with an emphasis on those from Canadian waters.

|

| The Redpath's Victorian lecture theatre. The first class for women students was held here, complete with chaperone, on October 6, 1884, James McGill's 140th birthday. Today, the theatre is still used for lectures, and is wired for multimedia presentations and video conferences, making for an unusual marriage of past and present styles.

|

|

| An epoxy resin cast of Albertasaurus sarcophagus from the Late Cretaceous period, a sharp-clawed, flesh-eating dinosaur in the tyrannosaurid family. Discovered in 1884 by Joseph Tyrrell in Alberta's badlands, Albertasaurus was the first carnivorous dinosaur discovered in Canada. The original of this 30-foot specimen is in the Royal Ontario Museum and was collected by Charles Sternberg along the Red Deer River in 1920.

|

| Grad student Temsin Rotheray at work on a fossil in a basement laboratory. The museum's paleontology collection includes 100,000 invertebrates from the St. Lawrence lowlands, 30,000 paleobotanical fossils from eastern Canada and 10,000 vertebrate specimens, as well as casts of early reptiles and amphibians.

|

|

| The mineral collection contains approximately 16,000 specimens, including material from the turn of the century, an important period for collecting. Many were gathered by Dawson himself. Gems, rocks and minerals from around the world are on display.

|

|