Medical informatics. The name doesn't sound very

inspiring. What it is, though, is something quite

revolutionary: a dramatic innovation that will

eventually change the way medicine is taught at McGill.

Aided by a $3.75 million grant from the Molson

Foundation, the Faculty of Medicine is placing its first-

and second-year curriculum, including lecture material

and full-colour, 3-D clinical simulations, onto CD-ROM

and the Internet. This will not only replace reams of

notebooks and flat images but, in the long run, alter

the function of teachers, who will be able to spend more

time in discussion and less on lecturing. "The idea is

to take the medical knowledge sitting in the heads of

our world-renowned experts," says David Fleiszer,

BSc'69, MD'73, MSc'79, Assistant Dean of Medical

Informatics, "and put it into the computer in an

interactive form."

Medical informatics. The name doesn't sound very

inspiring. What it is, though, is something quite

revolutionary: a dramatic innovation that will

eventually change the way medicine is taught at McGill.

Aided by a $3.75 million grant from the Molson

Foundation, the Faculty of Medicine is placing its first-

and second-year curriculum, including lecture material

and full-colour, 3-D clinical simulations, onto CD-ROM

and the Internet. This will not only replace reams of

notebooks and flat images but, in the long run, alter

the function of teachers, who will be able to spend more

time in discussion and less on lecturing. "The idea is

to take the medical knowledge sitting in the heads of

our world-renowned experts," says David Fleiszer,

BSc'69, MD'73, MSc'79, Assistant Dean of Medical

Informatics, "and put it into the computer in an

interactive form."

Although the program is unique in Canada -- several

American schools have the technology -- McGill and other

universities, including Sherbrooke, Laval and Montreal,

will develop a consortium to share the information.

Students will eventually have access to files from other

med schools, enabling each university to specialize and

become more efficient. The material will also be

accessible to doctors and patients.

A teaching module from the first four weeks of the

curriculum,"Molecules, Cells and Tissues," has been

developed as a demonstration; by September, several

teaching units will be available to students.

Most National, Most International

McGill students this academic year will experience the

most diverse student body of any Canadian university.

According to Registrar's Office statistics, McGill has

the most out-of-province students, some 36.2 percent at

the undergraduate level, and the most foreign students,

11 percentof the total student body. "We recruit

locally, nationally and internationally to encourage a

great number of high-quality applications," says

Director of Admissions Mariela Johansen. She says the

culturally varied city of Montreal is an attraction for

out-of-province students, many of whom have come through

French immersion and want to use the language.

Right on, Rhodes

Like proud parents announcing births, McGill is

delighted to present the two Rhodes Scholars for 1996:

Shariq Lodhi, 21, of Saint John, New Brunswick, and Lisa

Grushcow, 21, of Montreal. Lodhi is a dean's list

chemistry student who has competed in varsity rowing and

cross-country skiing. He plays the cello and organizes

concerts for the Royal Victoria Hospital Palliative Care

Unit which uses music therapy to comfort patients. He

hopes to become a doctor after studying at Oxford.

Grushcow is studying political science, with a minor in

Jewish Studies, and hopes to become a rabbi. She is

currently the Students' Society vice-president of

student affairs and has a wide range of extracurricular

activities, from journalism and acting to women's

groups. She will study within Oxford's Faculty of

Oriental Studies and Theology.

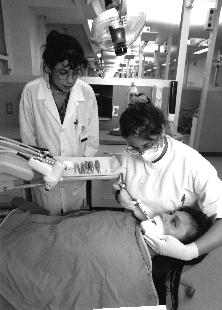

By the Skin of their Teeth

The closing of the Faculty of Dentistry was a done deal.

Or so most people thought

by Allen Konigsberg

July 17, 1991, could have gone down as Black Wednesday

in the 95-year Faculty of Dentistry history. Instead, it

became a footnote and major turning point that rallied

dental faculty, students, alumni and Montreal-area

supporters.

July 17, 1991, could have gone down as Black Wednesday

in the 95-year Faculty of Dentistry history. Instead, it

became a footnote and major turning point that rallied

dental faculty, students, alumni and Montreal-area

supporters.

On that 1991 day, Principal

David Johnston announced to the Dentistry professors

that the University governance had decided that the

Faculty would stop admitting students and close by 1996.

He said the high cost of educating dental students and

the Faculty's lack of research and post-graduate

programs left the administration no choice. In short,

Dentistry did not fulfill McGill's latest stated

priorities: to become a major research institution with

a high proportion of graduate students.

Present at the fateful announcement was Montreal dentist

Norman Miller, DDS'74, a McGill part-time lecturer. In

an interview from his Westmount office, Miller recalls,

"I asked what could be done to change the decision. They

said, 'Nothing. The money you could raise couldn't

possibly be enough.' But they couldn't answer me when I

asked how much money would be needed to save the school,

because they never thought of the possibility."

Miller organized a committee of fellow lecturers and

began a campaign to fight the decision." The benefits of

the school go to the public," says Miller. "We thought

the public should be informed." Graduates, too, would be

affected: Dentistry's closing could decrease the value

of the degrees of its 1,900 alumni. The support was

immediate. Miller's group raised nearly $20,000 to hire

a public relations person to communicate Dentistry's

merit. The implications of the loss of Quebec's only

anglophone dental school were well covered in the daily

media.

After vocal student demonstrations and alumni

protestations, the McGill administration came up with a

renewal plan for the Faculty in September 1991. It had

one year to fulfill eight conditions: decrease the

number of students from 26 to 24; develop a master's

degree program that would attract research funds;

increase faculty research; decrease the salaries of

casual lectures; establish criteria for evaluating

academic performance; ensure that the dental clinic

would become self-financing; arrange to rent clinic and

research space at the Montreal General Hospital; and,

finally, raise $1.6 million to upgrade equipment.

The apparent stumbling block was the last requirement.

But Nicholas Offord, Director of McGill's Development

Office at the time, drew up the fundraising game plan.

Offord recently told the McGill News, "What we tried to

impress on alumni was, 'Are you ready to let the Faculty

fall because of $1.6 million?' " "The community put its

money where its mouth was," Miller says. "We raised the

money in less than six months." In October 1992,

Principal Johnston announced that Dentistry had met its

conditions and would remain open.

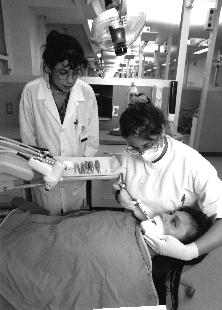

Last September, the Faculty introduced its new McCall

Dental Clinic at the Montreal General Hospital.

Generosity, and luck, played a large part in the

clinic's opening, which offers the latest dental

technology at a reduced cost to the public. A

significant portion of the facility's funds was donated

by McGill philosophy professor Storrs McCall, BA'52,

through The McGill Twenty-First Century Fund. Professor

McCall says, "I was looking to make a donation in the

field of medicine in the name of my parents [G. Ronald

McCall, BSc(Arts)'21, MD'39, DipPH'41, and M. Frances

McCall, BA'26, MD'42]. And the most pressing need was

the dental clinic, which serves the community and had

outdated equipment."

As per the other conditions, the Faculty now joins

several Canadian universities in offering a master's

program, and has more researchers on staff, including

new dean, James Lund. Part-time lecturers earn about

half of what they once made. "That wasn't a big deal,"

says Miller. "Even before, our staff was able to earn

much more doing clinical work than teaching. They do it

for the benefits of teaching at a university." Miller,

who is now the Faculty's first Associate Dean, Community

Relations, says, "What we face now is what the

University faces: budget cuts."

Dentistry is currently changing its curriculum, and

dental students now attend some medical school classes.

Their experience can be translated to other struggling

areas of McGill, says Miller. "Dentistry needed to

change the way it managed itself. I think that if the

issue is resources, it's fixable. It boils down to

finding alternative solutions."

Medical informatics. The name doesn't sound very

inspiring. What it is, though, is something quite

revolutionary: a dramatic innovation that will

eventually change the way medicine is taught at McGill.

Aided by a $3.75 million grant from the Molson

Foundation, the Faculty of Medicine is placing its first-

and second-year curriculum, including lecture material

and full-colour, 3-D clinical simulations, onto CD-ROM

and the Internet. This will not only replace reams of

notebooks and flat images but, in the long run, alter

the function of teachers, who will be able to spend more

time in discussion and less on lecturing. "The idea is

to take the medical knowledge sitting in the heads of

our world-renowned experts," says David Fleiszer,

BSc'69, MD'73, MSc'79, Assistant Dean of Medical

Informatics, "and put it into the computer in an

interactive form."

Medical informatics. The name doesn't sound very

inspiring. What it is, though, is something quite

revolutionary: a dramatic innovation that will

eventually change the way medicine is taught at McGill.

Aided by a $3.75 million grant from the Molson

Foundation, the Faculty of Medicine is placing its first-

and second-year curriculum, including lecture material

and full-colour, 3-D clinical simulations, onto CD-ROM

and the Internet. This will not only replace reams of

notebooks and flat images but, in the long run, alter

the function of teachers, who will be able to spend more

time in discussion and less on lecturing. "The idea is

to take the medical knowledge sitting in the heads of

our world-renowned experts," says David Fleiszer,

BSc'69, MD'73, MSc'79, Assistant Dean of Medical

Informatics, "and put it into the computer in an

interactive form."

July 17, 1991, could have gone down as Black Wednesday

in the 95-year Faculty of Dentistry history. Instead, it

became a footnote and major turning point that rallied

dental faculty, students, alumni and Montreal-area

supporters.

July 17, 1991, could have gone down as Black Wednesday

in the 95-year Faculty of Dentistry history. Instead, it

became a footnote and major turning point that rallied

dental faculty, students, alumni and Montreal-area

supporters.