|

It was a clear,

cool evening on Saturday, September 30, 1972, when Twinkle Rudberg,

BA'56, and her husband Daniel left their Westmount home together for

the last time. They were driving to have dinner with friends in downtown

Montreal when they saw a barefoot boy leap from the back seat of a parked

car and assault an elderly woman. It was a clear,

cool evening on Saturday, September 30, 1972, when Twinkle Rudberg,

BA'56, and her husband Daniel left their Westmount home together for

the last time. They were driving to have dinner with friends in downtown

Montreal when they saw a barefoot boy leap from the back seat of a parked

car and assault an elderly woman.

Daniel Rudberg stopped their car, jumped out and helped the dazed victim

to her feet. Then he chased the 14-year-old purse snatcher into some

nearby bushes. The two struggled, the teen pulled out a knife and within

minutes, Daniel Rudberg - husband, father, good samaritan - was dead.

He was 38.

Twinkle Rudberg thought her own life had ended. She was very angry

about what had happened, but, surprisingly, not at the lonely boy who

had killed her husband. During the teen's preliminary hearing and trial,

she learned that he was from a broken home, had turned to drugs, joined

a gang and run away from his home in the United States before coming

to Montreal. His violent act was apparently in imitation of something

he had seen on television. "The boy who murdered my husband was also

a victim," she says. Despite her shock and pain, she quickly realized

that she had a choice to make: she could either live the rest of her

life as a victim or use her newfound awareness of the devastating impact

of youth violence to try to spare others from the anguish. For her,

prevention was the only answer. "Otherwise what happened to me was without

meaning," she says. "Taking a hard line doesn't solve anything. It doesn't

benefit humanity." So she set up the Daniel Rudberg Fund for  research

into adolescent and child psychiatry soon after her husband's death.

She credits her "very strong (99-year-old) mother" for raising her to

deal with difficult situations and then keep going. research

into adolescent and child psychiatry soon after her husband's death.

She credits her "very strong (99-year-old) mother" for raising her to

deal with difficult situations and then keep going.

"I think that was part of my upbringing, to move on," Rudberg says.

And she did move on, but it was 20 years before she was finally able

to speak publicly about her husband's murder for the first time. She

was touched by the actions of 13-year-old Quebecer Virginie Larivière,

who in 1992 launched a campaign against violence on television after

her sister was raped and strangled. And that encouraged Rudberg to break

her own silence. Her story appeared on the front page of the Montreal

Gazette on September 30, 1992. She discovered, however, that talking

about the impact of violence wasn't enough.

|

Dim Light

Dim light alone

in the darkness

rattled by the screams

of terror echoing from the

silence that surrounds.

A crashing sound of dishes

shatters his nerves,

cracking the glass case

that contains the light

of his soul and

losing all hope he buries

his head in his pillow,

knowing that nothing

will save him.

|

"Dan's murder was influenced by a television program," Rudberg says.

"But I realized I was fighting a giant and I didn't want to become an

activist because it wasn't helping the kids." So she founded Leave Out

ViolencE (L.O.V.E.) in 1993. Each year about 20 teenagers aged 13-21

who are either victims or perpetrators of violence are recruited from

Montreal schools or referred by social workers, counsellors or teachers

to participate in the group's twice-weekly, after-school photojournalism

program. Held at Dawson College, it brings together teenage victims

of violence, perpetrators and witnesses to examine the causes of violence,

its impact and how to prevent it.

Recent incidents like the murder in November 1997 of Victoria teenager

Reena Virk and the shootings in Littleton, Colorado, and Taber, Alberta,

have focused public attention on the growing problem of youth violence,

and many are pointing a finger at violent television as a major culprit.

That's too simplistic, says Dr. Klaus Minde, DipPsych'65, psychiatrist-in-chief

of the Montreal Children's Hospital. "We should not imagine that having

less violence on television will do away with all kinds of social ills,"

he warns. What teens really need, he adds, is a place where they are

listened to, their opinions are valued and they can be taught appropriate

ways to handle conflict and anger.

If they aren't getting that at home, there are few other places where

they can. According to the Canadian Coalition for the Rights of the

Child, 70% of the funds that the Canadian government gives to the provinces

for youth justice is spent on custody. With rising public demand for

tougher penalties for young offenders it's likely that even less money

will be available to spend on prevention programs or alternative approaches.

Minde says being attracted to violent television is a manifestation

of a problem, not the cause of it. "The tendency of children who are

unhappy and angry is to select television programs that fit their own

inner life and they see it as a guide for their own behaviour."

Factors

that can contribute to children's unhappiness and anger include child

abuse, neglect, exposure to violence at home, poor parental care or

lack of social skills, Minde says. He described studies where young

subjects are shown a videotape depicting two children helping each other,

a second one with a neutral situation and a third one where two kids

are angry. Most children can correctly identify what is happening in

each of the three videos, says Minde. However, subjects with violent

tendencies perceive neutral situations as a prelude to a fight and believe

that they therefore have to act first. "They have a distorted view of

what the world is about and don't see things as they really are," Minde

explains. When a problem arises, they are reluctant to make any compromises

because they believe that "if I give a little bit he will take everything

and I will have nothing." Factors

that can contribute to children's unhappiness and anger include child

abuse, neglect, exposure to violence at home, poor parental care or

lack of social skills, Minde says. He described studies where young

subjects are shown a videotape depicting two children helping each other,

a second one with a neutral situation and a third one where two kids

are angry. Most children can correctly identify what is happening in

each of the three videos, says Minde. However, subjects with violent

tendencies perceive neutral situations as a prelude to a fight and believe

that they therefore have to act first. "They have a distorted view of

what the world is about and don't see things as they really are," Minde

explains. When a problem arises, they are reluctant to make any compromises

because they believe that "if I give a little bit he will take everything

and I will have nothing."

Participants in the L.O.V.E. program are given the opportunity to speak

out about violence in their lives, says Dawson College photography instructor

Stan Chase. "We give them a place to deal with their experiences through

writing and taking pictures." While one group of teens spends time learning

photography with Chase, the other works on their writing with program

director and Concordia University journalism professor Brenda Zosky

Proulx. It's here that teens write powerful stories about the violence

that surrounds them. "Sitting on the floor, surrounded by light, or

next to the photo lab is where some of the best writing happens," Proulx

says.

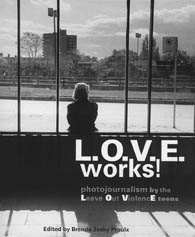

By the end of the year participants are able to take pictures, develop

film and print contact sheets, Chase says. "They're usually doing the

same work as a first-year college student," he observes. "These are

kids that are labelled underachievers, but when you see what they produce

for us, they're definitely not underachievers." The result is L.O.V.E.

Works! a poignant collection of photographs, essays and poems by 58

teens from the program's photojournalism project. Edited by Proulx and

released by Stoddart Publishing Co. in 1998, it's dedicated to the memory

of Daniel Rudberg and to youth who are affected by violence on a daily

basis.

Julia, 19,

who joined L.O.V.E. about three years ago, was one of those young people.

She had been placed in a group home after rebelling, frequently running

away from her family, stealing a car and doing drugs. She was raped

at the age of 14 by an acquaintance at whose home she had sought refuge.

It was within the accepting and respectful environment of L.O.V.E. that

Julia was able to turn her life around. "I would drag my feet going

home," she recalls. Today, the affable blonde lives with her family

and credits the program and having found God for setting her straight.

Now she spreads the gospel about L.O.V.E. and the effects of violence

on society to students at Montreal schools as part of the organization's

outreach team. Julia, 19,

who joined L.O.V.E. about three years ago, was one of those young people.

She had been placed in a group home after rebelling, frequently running

away from her family, stealing a car and doing drugs. She was raped

at the age of 14 by an acquaintance at whose home she had sought refuge.

It was within the accepting and respectful environment of L.O.V.E. that

Julia was able to turn her life around. "I would drag my feet going

home," she recalls. Today, the affable blonde lives with her family

and credits the program and having found God for setting her straight.

Now she spreads the gospel about L.O.V.E. and the effects of violence

on society to students at Montreal schools as part of the organization's

outreach team.

Accompanied by staff member Maureen Labreche, teams of four students

visit the same classroom three times over a one- to two-week period.

During the first session they talk about L.O.V.E., show students 20-25

photographs taken by participants in the photography program and discuss

their significance. Then team members share their own experiences. "It's

so powerful that there's not a dry eye in the house afterwards," Labreche

says. "That's why this program works."

| Alone

They shout,

She cries.

They call her names,

She cries.

No one knows why.

She goes to school

and puts on a show,

They think she's happy

but nobody knows.

She goes back home

and feels so low

and all alone

Nobody knows.

It's time for bed,

and nobody knows.

Nobody knows.

Nobody knows.

|

The key to its success goes beyond the power of the message. It's the

messenger who really matters. Julia thinks that having teens talking

to teens makes a big difference. "It's the first time students see people

their own age rather than adults condescendingly talking about violence,"

she says. Daniel Guinta, 16, agrees. He joined Leave Out ViolencE a

year ago after participants came to speak at his school. "I could relate

to them because they were my age," he says. Six months later, the articulate

high school student joined the outreach team.

The second visit focuses on writings about violence. Labreche writes

some unfinished sentences on the blackboard to encourage students to

write about their own experiences with violence. They include "I am

worried about violence because I remember when..." and "We are having

trouble with youth violence because we don't...." Elementary school

students can also opt to write a letter to their parents. "Sometimes

I die inside from the things I read," Labreche says. "They have experienced

a lot of violence in their families." Students can be put in touch with

support services, if they are interested in getting help.

For the final session, students listen to some popular music, mostly

rap, to discuss the violent lyrics the songs contain. They are also

shown a video about the level of violence displayed in the media. Then

students are invited to join L.O.V.E.

The seeds of Twinkle Rudberg's philosophy about handling tragedy are

perhaps evident in the quote she chose for her entry in the Old McGill

yearbook. "The mind is its own place and in itself can make a heav'n

of hell, a hell of heav'n." When asked if she recalled why she had chosen

that particular passage, she responds with a puzzled "I have no idea,"

but she recognizes an eerie connection between the words from Milton's

Paradise Lost and the work she is now doing. "I chose to take something

that happened to me that was hell and turn it into something positive - and we're doing the same thing with kids," she

says. Starting in January, she will be able to extend the photojournalism

project to youth in Halifax and Vancouver, thanks to a $1 million grant

from the Millennium Bureau of Canada. "Our millennium project is to

have 2,000 L.O.V.E. youth across Canada be spokespeople for the elimination

of youth violence," Rudberg says. A franco-phone program was launched

in Montreal this summer and one has been operating in Toronto since

1997. But Rudberg doesn't plan to stop there. She says the shootings

in Colorado and Alberta have made her more determined than ever to make

Leave Out ViolencE available to as many teens as possible. It is important

to empower young people, she says, for it is they who will provide the

answers to stemming the tide of youth violence. "I don't think adults

alone can make a difference here. We have to listen to our youth and

let them tell us what has to be done."

something positive - and we're doing the same thing with kids," she

says. Starting in January, she will be able to extend the photojournalism

project to youth in Halifax and Vancouver, thanks to a $1 million grant

from the Millennium Bureau of Canada. "Our millennium project is to

have 2,000 L.O.V.E. youth across Canada be spokespeople for the elimination

of youth violence," Rudberg says. A franco-phone program was launched

in Montreal this summer and one has been operating in Toronto since

1997. But Rudberg doesn't plan to stop there. She says the shootings

in Colorado and Alberta have made her more determined than ever to make

Leave Out ViolencE available to as many teens as possible. It is important

to empower young people, she says, for it is they who will provide the

answers to stemming the tide of youth violence. "I don't think adults

alone can make a difference here. We have to listen to our youth and

let them tell us what has to be done."

|

The Jacket

It was late at night when I lost my best friend,

my world. Clifford, a high school drop-out who was trying to support

his mother due to his father's death three weeks earlier, was

on his way to his car to go home when he was brutally slaughtered.

When his body was found, he had been stabbed 16

times in and around the heart. His own mother could not even recognize

him due to the bruises covering his face. She noticed that he

wasn't wearing his jacket. When I got the phone call, I felt as

if my soul had been ripped out of me and sent to a far-off place

where I could never find it again and I haven't, nor will I ever.

Eventually a confession was made. The perpetrator

said, "I wanted his jacket. I didn't mean to kill him." I cannot

seem to understand why or how, but this is a problem in our society,

and I will contribute all of myself and all within my power to

make a difference.

|

|